A Socio-Behavioral Approach to Understanding the Spread of Disinformation

Copyright ⓒ 2021 by the Korean Society for Journalism and Communication Studies

Abstract

Although the development of digital technology has increased communication efficiency, confusion caused by the rapid circulation of misleading information is hindering the sustainable development of modern society. Therefore, scholars have recently begun to pay attention to understanding the behavior of the public concerned with disinformation spread. In this context, the present paper attempts to provide a theoretical insight into the public’s motivations to spread disinformation and how these interact with socio-institutional variables, such as trust in government and media literacy, in the process of disinformation spread. Based on the evaluation of the traditional and modern literature on different types of information sharing behaviors as well as the key factors that are unique to the context of disinformation spread, we propose a conceptual framework of the socio-behavioral mechanism underlying the public’s communication of disinformation from the perceptual to communication level. Lastly, we suggest adequate government interventions based on the framework and a new culture that our society should endorse to be protected against the risk of disinformation. The current research will provide a foundation for the further development of human-centered solutions in the field.

Keywords:

disinformation, information behavior, rumor, motivation to spread disinformation, word-of-mouth, trust in government, media literacyIn the first week of April 2020, millions of people from all over the world viewed a video showing two female doctors being attacked while tracing a person who had come into contact with a coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) patient in Indore, India. The incident was said to have been triggered by fake WhatsApp videos alleging that healthy Muslims were being captured by medical personnel, injected with the virus, killed, and later dumped (Web Desk, 2020). As a result, innocent citizens who were trying to help fight the disease were put in danger. This is but one case involving fake news, warning global citizens of the danger of not just the pandemic but also the “infodemic” (Zarocostas, 2020), which jeopardizes the operation of open democratic societies.

As a response to the prevalence of disinformation, governments have been trying to come up with adequate solutions to limit the dissemination, which include employing artificial intelligence (AI) for content scanning (Park et al., 2018), criminal penalties and significant fines for anyone convicted of spreading fake news (in Singapore), and restricting postings by specific groups of people (in the US; Banjo, 2019). While these solutions may limit the spread to a certain extent, further progress will be difficult unless the role of the audience (i.e., digital users) is better understood (Jones-Jang et al., 2019). Consequently, researchers in the field have recently started paying more attention to the public’s role in disinformation spread, such as examining psychosocial variables that might be linked to one’s tendency to believe unverified information and communication behavior associated with it.

To propose and develop adequate solutions to the problem with a long-term perspective, a global picture of what drives citizens to communicate unverified information would be critical. The current literature, however, is still segmented in a sense that different stages of the distribution of disinformation is studied independently with limited viewpoints. Thus, the present paper attempts to provide a more holistic view on the phenomenon by presenting an organized analysis of the socio-behavioral metrics associated with each stage of the process of disinformation transmission.

We begin this article by assessing the current state of modern digital disinformation. Then, we examine a psychosocial mechanism underlying the behavior of the public in response to disinformation by exploring the traditional domains such as the literature on rumor and word of mouth (WOM), and compare them with the recent trend of unverified information sharing. This analysis will additionally inform on the key factors that are more unique to the context of disinformation spread. Next, based on the evaluation of literature, we propose a conceptual framework of the socio-behavioral process of the spread of disinformation, which presents perceptual, motivational, and communication stages of disinformation spread. Further, the process by which essential socio-institutional variables, such as trust in government and media literacy, impact citizens’ communication behavior will be explored within the framework. Lastly, we suggest adequate government solutions to protect the community from the risk of disinformation based on the proposed framework. In this paper, we limit our definition of disinformation to deceptive and misleading information about public issues that could instigate miscommunication and misunderstanding among citizens, which can impact the operation of a country.

What is Disinformation?

Disinformation refers to false or misleading (although not necessarily incorrect) content aiming to deceive or manipulate. It can easily be confused with misinformation, which denotes inaccurate information resulting from an honest mistake of the source (Banjo, 2019; Fallis, 2009). Although these two types of content can be similar in terms of accuracy, the technique for identifying their authenticity can be different. It is often more difficult to detect disinformation, as the source expends significant effort to make the material appear believable so that people misperceive the topic (Fallis, 2015).

As mentioned, actors with strong intentions to deceive and mislead others create disinformation. Some individuals may desire to profit from the content, while other individuals would generate such content for personal entertainment and satisfaction. For instance, Internet trolls, conspiracy theorists, and hyperpartisan groups create and post content to influence the public based on the group’s principles and for personal satisfaction (Marwick & Lewis, 2017; Phillips, 2015). In other cases, politicians or foreign governments pay hired trolls or employ bots (pieces of computer software) to disseminate contents that are in favor of their position and agenda (Marwick & Lewis, 2017). Lastly, some actors run fake news websites simply for money, earning advertising revenue from people visiting their websites to read the articles (Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017). While scholars are constantly investigating the origins and behavior of these groups, progress in understanding the true scope of these actors is hindered due to diverse tactics, platforms and patterns of behavior employed by different sources.

Disinformation is not a modern concept: hard-copies of manipulated photographs, misleading advertisements in newspapers, and government propaganda have clouded people’s judgment and decision-making in the past as well. In recent years, this phenomenon has developed through online media and various social platforms. What is more, there is a general decrease in journalism (Baek, 2021; McLennan & Miles, 2018). Thus, people seek information of interest from various online websites, which lowers the hurdle for the infiltration of disinformation.

Digital technology makes it much easier to manipulate and disseminate false information as well. Photographs are easily altered (Farid, 2008), and videos and audio recordings can also be doctored or created using AI-based technology (deepfake), thereby posing a whole new level of threat (Blitz, 2018). Simultaneously, publishing misleading information has been simplified: fake news websites are calibrated to look reputable (Fowler et al., 2001), and people can anonymously add information, often regardless of its accuracy, to various online encyclopedias (Fallis, 2008). Further, social network services such as Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp have largely replaced traditional person-to-person interactions, serving as news-sharing tools (Kim et al., 2021; Kwon et al., 2017). Consequently, with fewer barriers to mass communication, purveyors of disinformation can reach a huge audience anonymously or in disguise.

Psychological Motivations underlying Disinformation Spread: Insights from Literature on Rumors and Word-of-Mouth

From the general public’s (perceiver) point of view, there are many similarities between disinformation and rumor. A rumor constitutes a proposition that is unconfirmed due to a lack of immediate explanations from credible sources and has topical relevance to persons involved in spreading behavior (DiFonzo & Bordia, 1998). Similarly, disinformation is information that has not been verified, which usually constitutes content that is relevant to the persons involved in disseminating (e.g., public issues). In this vein, both concepts assume that the content of information could result in the feeling of uncertainty. It has been suggested that rumor-spreading behavior offers a sense of control in uncertain situations, easing the anxiety and uncertainty associated with the rumor itself (Rosnow, 1991). This implies that the current media environment, in which sources are often unidentifiable, is fundamentally associated with societal anxiety, creating an environment that aids dissemination.

Viewing rumor behavior as a type of social interchange, Bordia and DiFonzo (2005) have identified three basic psychological motivations for the dissemination of rumor: fact-finding, relationship-building, and self-enhancement. The next section will review the literature on rumor within the framework of these three motivations.

Fact-Finding Motivation. Decades of research on rumor spread has pointed uncertainty as the central element of psychological explanations (Allport & Postman, 1947; Bordia & DiFonzo, 2005; Rosnow & Fine, 1976). An old field experiment by Schachter and Burdick (1955) demonstrated that a planted rumor spread twice as much in conditions of uncertainty (staged), and rumor-related discussions on the Internet were found to be constantly dedicated to seeking and evaluating the rumor in an attempt to reduce uncertainty regarding the topic (Bordia & DiFonzo, 2004). Similarly, with the emergence of the COVID-19 outbreak, the proliferation of disinformation regarding preventative cures and tips to fight the disease has been observed, reflecting their anxiety and fear towards the life-threatening and, yet, an indeterminate disease (Lampos et al., 2020). Consequently, Vosoughi et al. (2018) designated novelty of information as one of the main factors resulting in the dissemination of fake news online.

Studies that have directly examined information-seeking motivation in social media usage found that, indeed, one of the core reasons why people spread unverified information was to be updated with the newest information about a topic of interest (Apuke & Omar, 2021; Ma et al., 2013; Yum & Jeong, 2019). This act of spreading would involve both reception and propagation, which could satiate the person’s need to be ‘in the know’ (Duffy et al., 2020). In the face of a personal or collective danger that requires understanding or situational knowledge of the events, rumors seem to function as predictions and collective warnings, which enable people to prepare and take effective action in time (Walker & Blaine, 1991). Although the rumor process itself is not a sufficient tool to obtain accurate explanations, it can be part of a problem-solving process aimed at reducing uncertainty (Bordia & DiFonzo, 2005).

Relationship-Building Motivation. The ability to build and maintain relationships is central to the survival of social mammals. It encourages various social behaviors, such as compliance with norms (Cialdini & Trost, 1998) and impression management. Relationship-building motivation also plays a critical role in rumor behavior because rumor transmission is a type of social encounter: the decision to pass on a rumor is influenced by the consequences of dissemination on interpersonal relations. “Minimize-unpleasant-messages” is often observed in this aspect, which depicts people’s tendency to transmit messages that are positive towards in-group goals because of the fear that being a bearer of bad news could result in a negative impression (Tesser & Rosen, 1975). Nevertheless, negative messages are shared if the information is considered helpful to those who we care (Weenig et al., 2001) and if they match the affective context; in other words, rumors congruent with the mood of the conversation (e.g., a conversation about the severity of COVID-19) are likely to be shared as a way to enhance interpersonal relationships with the people in the conversation (Heath, 1996).

In relation to social media usage, it was shown that there was a positive association between social interaction motive and the use of social media. Regardless of the falsity of news, news sharing was shown to confer socialization gratification, through which people maintain and extend their relationship with others (Apuke & Omar, 2021; Lee et al., 2011; Yum & Jeong, 2019). Further, individuals with higher socializing nature were more likely to believe unverified media content (Lai et al., 2020) and were shown to share various contents more often on their social media (Correa et al., 2014). People have a desire to maintain their credibility within their social circle and be known as someone who holds valuable information, so that they can remain a valued, reliable, and influential member of the social network (Stevens & Fiske, 1995), which again emphasizes the role of relationship building motive underlying the people’s usage of social media and rumor dissemination behavior (Chang et al., 2017).

Self-Enhancement Motivation. Humans have the need to feel positive about themselves which motivates the adjustment of cognition in ways that bias decision-making processes (Dunning, 2001). For instance, we tend to trust information favorable to the self and employ heuristics that lead to favorable judgments (Kunda, 1999). The processing of rumor also operates under the motivation of self-enhancement. People assess rumors based on their existing beliefs and by sharing such rumors their self-esteem can be boosted (Allport & Postman, 1947). Lee and Ma (2012) showed that people with higher motivation for status-seeking tended to spread news more often on social media and N. Thompson et al. (2019) demonstrated that status-seeking was one of the gratification factors that was associated with news sharing behavior. Similarly, Yum and Jeong (2019) reported a positive relationship between self-enhancement motivation and self-reported fake news sharing behavior.

Rumors can sometimes justify prejudice and discrimination as well. According to social identity theory, we derive self-esteem from belonging to groups and engage in in-group favoritism (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). A rumor describing negative aspects of the out-group can rationalize in-group favoritism; we indeed encounter a larger number of rumors hostile towards out-groups. For instance, the top disinformation spreaders on Twitter during the 2016 US presidential election were found to be the Trump supporters, spreading various fake news and conspiracy theories against Clinton. Simultaneously, a large amount of extremely biased news was shared by the Clinton supporters, demonstrating the usage of social media as a way to manifest in-group favoritism (Bovet & Makse, 2019). In short, rumors tend to be self-serving and, sometimes, derogatory to the out-group, as part of fulfilling the motivational goal of self-enhancement (Bordia & DiFonzo, 2005).

Word-of-Mouth (WOM) is a prominent concept in communication, marketing, and management. It is defined as person-to-person communication about an evaluation of a product, company, or service (Shen et al., 2016). Like rumor behavior, WOM is a non-commercial way to share ideas, opinions, and information between individuals (Engel et al., 1969). People attempt to communicate their opinions about personal experience with the product with the active audience (consumers), who look for specific information to guide their purchasing decisions. In this vein, WOM resembles both rumor and disinformation spread as the key audience of these concepts are people who have a genuine interest in the topic of conversation. Therefore, examining the literature on motivations for WOM could provide additional insight into the mechanism of disinformation dissemination (see Table 1).

Traditionally, four categories of positive motivations for WOM have been put forward. First, the motivation to regulate emotions from product involvement and concerns, helping ease the sharer’s tension or express enthusiasm about the experience. Second, self-enhancement plays a role as the sharers seek to gain attention as connoisseurs from other active audiences who look for that information. A third motivation revolves around message involvement, manifested in sharing unique and appealing advertisement messages regarding the product or service (Dichter, 1996). Lastly, motivation to help others contributes to people’s willingness to engage in WOM (Price et al., 1995): people share market information and explain the pros and cons of different brands to other potential consumers who are interested in purchasing the product.

Different scholars have identified additional motivations, which may vary depending on the valence of WOM (i.e., positive vs. negative) or cultural differences. For instance, Sundaram and colleagues (1998) found that consumers engage in negative WOM out of altruism, for vengeance, or to alleviate anger, anxiety, and sadness. Cheung and colleagues (2007) examined the similarities and differences in motivations for WOM between the US and Chinese consumers: while both countries shared similar motivations, including altruism, strengthening social ties, seeking a sense of achievement, and a therapeutic effect, Chinese consumers exhibited additional motivations for positive WOM such as seeking advice and confirmation of their own judgment. Regarding negative WOM, US consumers showed additional motivations like seeking compensation and bargaining power, while Chinese consumers sought confirmation of their judgment, advice, and retaliation. Consequently, motivations for WOM may vary depending on the context and type of WOM that the transmitter attempts to communicate.

While some of the WOM motivations discussed may be specific to consumer goods, such as seeking compensation for faulty products, others can be more generally applied to both rumor and disinformation. For instance, self-enhancement has been identified as a motivation for WOM as well as rumor spread. Similarly, motivation to share unique and appealing advertisement messages of the product or service (Dichter, 1996) could promote one’s self-esteem by implicitly displaying the status of ‘early adopter’ that has the most up-to-date information. Thus, we suggest that self-enhancement could be a crucial motivation for disinformation spread. Additionally, seeking advice and confirmation of one’s judgment could overlap with the fact-finding motivation identified in the rumor model elaborated by Bordia and DiFonzo (2005): the uncertainty associated with their decisions to use the product leads people to seek advice to relieve the associated anxiety. Therefore, we suggest that fact-finding motivation could also be applied to understand the spread of disinformation.

More importantly, some of the motivations uniquely identified in the WOM research are worth being considered to explain disinformation spread. WOM’s possible role in helping vent emotions derived from product involvement (e.g., terrible service), including anger and sadness, has been discussed previously (Dichter, 1996; Sundaram et al., 1998). Given the communal aspects of coping, the social sharing of emotion offers a valuable channel for sharers to manage their emotions: it can generate social support, assist in making sense of the situation, reduce dissonance, and help vent emotion (Berger, 2014). Fake news was shown to inspire fear, disgust, and surprise, as evidenced in reactions to the news contents shared as online comments (Vosoughi et al., 2018). Thus, it can be inferred that the act of discussing and conveying unverified information can help let out emotions associated with it.

Lastly, the motivation of helping others was shown to underlie WOM such that people would share the information to help other customers make better purchasing decisions. Kimmel (2004) stated that sharing information, in general, can help others. In the context of news sharing, Apuke and Omar (2020) showed that people in Nigeria habitually share news out of civil obligation to warn others and provide advice without checking the validity of information, and such motivation was evidenced again in COVID-19 fake news sharing behavior (Apuke & Omar, 2021). This suggests that intention to help others could be another significant motivational factor that influences people’s judgment of passing disinformation.

With the advancement of digital technology, rumor and WOM are transmitted actively online through social networking systems and various forums. In relation to this, several additional situational factors need to be considered. First, unlike offline physical communication, messages or posts that transmitters upload can be anonymous. For instance, messages may be posted using an alternative online identity, without revealing the poster’s true identity. Second, several people can receive or view the same post, which can be accessed from anywhere at any time (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004). While the number and type of people that can be involved in physical person-to-person communication are limited, there is no clear boundary for online communication. Third, digital rumors and electronic WOM (eWOM) can persist longer and are significantly more detailed, given that the material is posted and saved in an electronic form, whereas their traditional counterpart is shorter and passed from person to person (Cheung & Thadani, 2012). Consequently, lurkers (users who read posts without contributing) can potentially become posters (people who post messages) at any time, thereby increasing the population that transmits such information.

Aforementioned circumstances imply that digital rumors and eWOM are much more influential than their traditional forms because of their prevalence, convenience, speed, and absence of face-to-face communication and pressure (Lee et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2016). This suggests that the battle against the spread of disinformation in the current era would involve not only the traditional psychological underpinnings of the communication of unverified information but also the aspect that concerns the new media environment.

Although disinformation, rumor, and WOM share several similarities, a few key aspects set the current topic of disinformation apart. To help draw a conceptual framework of the spread of disinformation, we will pinpoint these crucial factors.

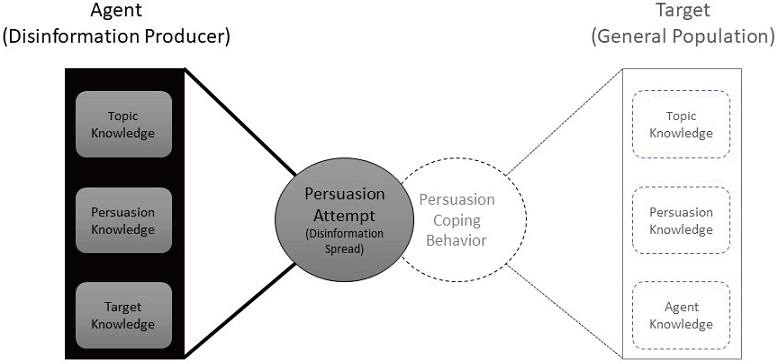

The Public’s Lack of Situation Awareness. Producers of disinformation have strong purposes for their activities, such as an intention to deceive and manipulate the target. Consequently, misleading information is usually presented in a good disguise (Faris et al., 2017), which makes it difficult for the public to differentiate disinformation from real information. Therefore, there is an imbalance of situation awareness between the producer and the target of disinformation. According to the Persuasion Knowledge Model—PKM—(Friestad & Wright, 1994), the targets’ persuasion coping behaviors develop continuously as various experiences increase their persuasion knowledge. Similarly, Roozenbeek and van der Linden (2019) point out that the experience and knowledge on the production of fake news could improve people’s ability to spot and resist disinformation. However, people often do not notice that they have been exposed to disinformation and unless people actively try to ascertain the authenticity of misleading content, there is a high chance that fake information will be remembered as factual. Thus, it is difficult for the public to execute or develop appropriate coping behaviors towards disinformation, which puts the public at a great disadvantage (Figure 1).

The Persuasion Knowledge Model of Disinformation Spread Note. The persuasion knowledge model reflecting the spread of disinformation, adopted from the original persuasion knowledge model by Friestad and Wright (1994). Unlike the original model, the target’s (the public’s) knowledge and coping behavior are dormant. Contents in the dashed lines are dormant due to lack of awareness.

Importance of Public Trust in Government. Disinformation in the current context refers to false or misleading information that targets public opinion. As such, it can be extremely dangerous because it concerns important public issues and may misguide a large population into making harmful judgments. For instance, disinformation on vaccines has not only amplified social discord but also put citizens’ health at serious risk. An analysis of vaccine-related Twitter posts from 2014 to 2017 (Broniatowski et al., 2018) revealed that social media bots and Russian trolls that had attempted to influence the US election spread disinformation about the safety of vaccination, thus exposing people to the danger of infectious diseases. Despite the advice of public health officials, the number of children exempted from vaccines has seen a constant increase since the onset of the vaccine debate. This example case indicates a close association between trust in government and the impact of disinformation on citizens: disinformation can impair the public’s trust in government, while lower trust in government can aid the spread of disinformation and strengthen its impact on citizens.

Lack of trust in government poses various challenges for the functional operation of a country: increasing distrust results in hindered adoption and implementation of government-initiated tasks (Lallmahomed et al., 2017; Park & Lee, 2018). As evidenced in the vaccination case and more recent reports that claim that COVID-19 related fake news had resulted in over 800 deaths in 2020 alone (Coleman, 2020), citizens’ health can be jeopardized when fake information is trusted over the correct information published through official routes. Thus, the initial level of trust in government could be a critical factor affecting the rate at which disinformation spreads among citizens.

Media-Related Literacies. The importance of literacies associated with the intake, appraisal and communication of various media contents have gained attention within the last decade due to increased exposure to information from numerous sources (Jones-Jang et al., 2019; Koltay, 2011). As users of Internet, the current generation needs to adapt to the new media environment where individuals are anticipated to consume and produce, share and criticize digital media content (Koc & Barut, 2016). Different researchers focus on different domains of media-related literacies such as media literacy, digital literacy, information literacy and news literacy. The key message from this field of research is that the public should acquire adequate capacity to process media information to combat inaccurate information. Guess and colleagues (2019) have pointed media literacy as the main factor underlying the sharing of fake news on Facebook even when variables like educational level, ideology, and partisanship are accounted for. Other studies have shown that media literacy interventions were shown to improve one’s behavior towards dealing with unverified information (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2019; Yum & Jeong, 2019). Therefore, media-related literacy seems to have a vital role in the public’s disinformation spread behavior.

A General Conceptual Framework: The Psychosocial Process of the Spread of Disinformation

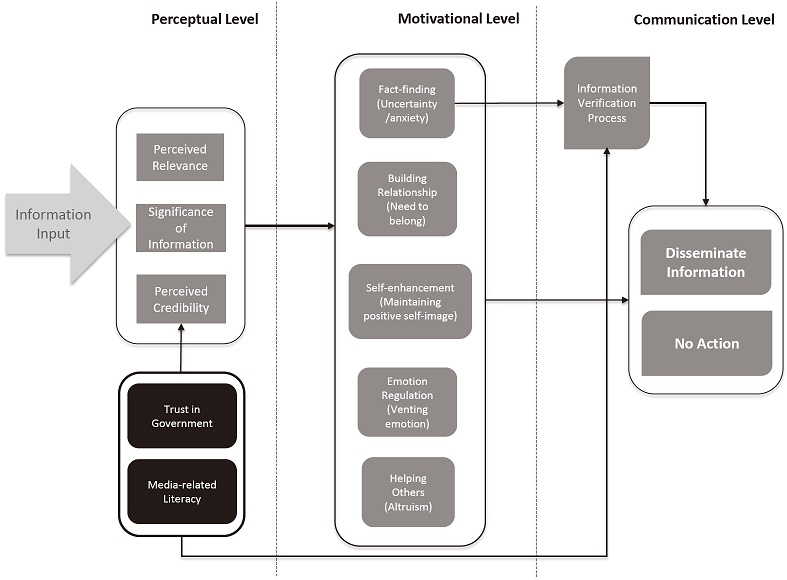

Based on the preceding review of the literature on disinformation and related social behaviors (rumor and WOM), we will draw a conceptual framework that identifies various socio-behavioral factors underlying the spread of disinformation among the public (see Figure 2).

Three factors regarding the content of disinformation can determine the perception of information: perceived relevance, significance of information, and perceived credibility. These are the critical elements that determine people’s attention towards any given piece of information (Bordia & DiFonzo, 2005). First, perceived relevance of the information indicates the association between the piece of information and the perceiver’s survival in his/her social world, thus, increasing their desire for knowledge (Dunning, 2001). Similarly, the significance of the information plays a critical role: people tend to gear their attention towards heated subjects as part of their efforts to relate to others and claim their social identity (Cialdini & Trost, 1998). Moreover, it is often correlated with the importance of the topic. Lastly, the perceived credibility of the content can influence people’s judgment of the information because credibility is directly related to the believability of the information. The credibility of the source, which is closely linked to that of the content, is one of the critical factors that lead to successful persuasion (Hovland et al., 1953).

While these three factors determine the perception of information, there are additional individual factors, media-related literacy and trust in government, that could modulate this perceptual process by interacting with the perceived credibility of the information. As highlighted previously, media-related literacies have shown to improve individuals’ intake, appraisal and communication behavior associated with information in the new media environment (European Commission, 2008; Jones-Jang et al., 2019; Koc & Barut, 2016; Yum & Jeong, 2019). As a skill that could be acquired, it plays a crucial role in determining one’s perception of the trustworthiness of information in the media environment by providing more critical insight. Thus, it could be deduced that media-related literacy would influence the perception of information credibility in the current framework.

Similarly, trust in government can modulate the perceived credibility of information. Citizens with a higher level of trust in government tend to value information and standard operating procedures (SOP) published by public agencies (Güzel et al., 2019). This suggests that the way people perceive information at hand will differ depending on the level of trust in government: those with higher trust are more likely to be critical toward information from unknown sources. In this vein, trust in government could play a crucial role in influencing the perception of disinformation, which, subsequently, affects the instigation of motivations to spread.

Once the disinformation is perceived, motivational variables will operate. Based on our literature review, we propose five motivational factors, which are fact-finding, building relationship, self-enhancement, emotion regulation and helping others. As discussed, modern media content is fundamentally associated with anxiety due to the numerous sources of information that cannot be determined easily. In such an environment, the goal of fact-finding becomes active and plays a significant role as one of the motivations for disseminating disinformation (Allport & Postman, 1947; Rosnow & Fine, 1976). Next, we suggest that the intrinsic motivation to build and maintain relationships can play a critical role in spreading disinformation as part of a social encounter (Cialdini & Trost, 1998). To be able to maintain their credibility as someone who holds valuable information and to comply with the norms of the group, people are likely to communicate intriguing information that they encounter to their social circle (Stevens & Fiske, 1995). Especially, with an increase in the usage of social networking services (SNSs), such motive can be amplified as these services expose individuals’ activity in their community. Lastly, a self-enhancement motivation could play a role in the current stage. To boost and maintain one’s self-esteem, people like to share information that rationalize their existing beliefs and favorable to the self or their in-group (Allport & Postman, 1947; Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Again, SNS can aid fulfilling this motivation by providing a platform that they can actively operate (Lee & Ma, 2012). In short, the main motivational variables evidenced in rumor psychology can have a significant impact in individuals’ willingness to spread disinformation.

In addition, motivation to regulate emotion as discussed in the literature of WOM can have an impact (Berger, 2014; Dichter, 1996). Sharing information with others should aid emotion regulation by facilitating sense-making, generating social support, reducing dissonance, and venting emotion (Berger, 2014). Fake news has been known to trigger various emotions such as fear and surprise, which were observed in numerous comments people share about the news (Vosoughi et al., 2018). Therefore, the motivation to regulate emotion may also drive disinformation spreading behavior, which allows the transmitter to vent emotions triggered by exposure to the disinformation.

Lastly, the desire to help others identified in the WOM literature could be one of the main motivations to spread disinformation (Hennig-Thurau et al., 2004; Price et al., 1995). People who have personal experience with the product or service believe that their knowledge can be truly valuable to potential consumers. Disinformation tends to be perceived as trustworthy by a naive audience because of its convincing disguise and presentation (Fallis, 2009, 2015). Consequently, people exposed to disinformation are likely to believe that sharing the information will benefit others. Therefore, we suggest that helping others out of altruism can be the main motivation for spreading disinformation.

Once disinformation is perceived and processed, the combined levels of motivations would determine the subsequent communication action of spreading the information. In addition, an alternative behavior – verification of unverified information – may be observed prior to the final decision on dissemination. For instance, an individual with higher trust in government tend to value governmental information more and is likely to make use of various government sources (e.g., e-government; Park & Lee, 2018; West, 2004) to obtain information. Such individual tends to show higher compliance with the government-initiated tasks and orders (e.g., recommended use of e-government in crisis). This suggests that people with a higher level of trust are more likely to validate the unverified information through official government sources before they take further action as recommended. Similarly, people with higher media-related literacy, who are more knowledgeable of the context of the new media environment and its impact on society, have the ability and motivation to critically appraise the information (Koc & Barut, 2016). This could, therefore, lead to the confirmation of information through more validated sources, such as an established fact-checking website and e-government tools, before making the decision on transmission. In essence, these two individual factors modulate the ways in which the credibility of information and its source are perceived due to the differences in the frame of judgment, and this could contribute to the action of validating unverified information.

Lastly, we suggest the fact-finding motivation to be one of the most relevant motivational factors to the onset of verification behavior. Essentially, the underlying motive for verification is to fact-check about a piece of information that one is unsure about. (DiFonzo & Bordia, 2007; Kruger, 2017). In this vein, it could be deduced that those with a higher level of fact-finding motivation will be more likely to engage in information verification behavior. In short, trust in government, media-related literacy and motivation to fact-find can interplay to drive verification behavior.

Government Interventions to Tackle Disinformation Spread

In the coming sections, we suggest and discuss possible government interventions to moderate the behavior of citizens concerning the communication of disinformation. By pinpointing variables that have been addressed in the conceptual framework, we will suggest necessary measures to impede the spread of disinformation.

As previously explained, fact-finding has been identified as one of the critical motivations in spreading disinformation. Because disinformation about public issues usually consists of a reasonable but unverified proposition of high relevance to individuals, the uncertainty it creates easily leads to societal anxiety. Given the problem of increased uncertainty, it would be important for government bodies to tackle the general sense of insecurity among the public. For instance, the correct information of the raised issues should be readily available to the public and its source should be perceived as reliable and approachable as the communicator is a critical feature that determines the success of persuasive communication (Hovland et al., 1953).

As part of the policy responses, OECD has recommended several measures to reduce anxiety associated with information related to COVID-19 (OECD, 2020). There are already some fact-checkers that provide unbiased analysis of information and help online platforms identify false content. Yet, the public does not actively utilize them due to the lack of support in promoting these organizations and websites (Schuetz et al., 2021). Thus, governments and authorities should help by supporting these fact-checkers and rely on their information analyses to repair public trust and reduce uncertainty associated with it. Further, it has been suggested that a use of standardized trust mark for the content that has successfully passed fact-checks by several independent fact-checking organizations would be useful as it has been shown to be effective in increasing consumers’ trust in the e-commerce context (F. M. Thompson et al., 2019).

While the government and international authorities can promote the usage of fact-checkers, the utilization of e-government may also be desirable (Lallmahomed et al., 2017; Park & Lee, 2018). Indeed, the development and promotion of e-government and social media were shown to have a significant improvement in public’s attitude to adopt protective behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic, which demonstrates the importance of e-government during a crisis when anxiety is high (Mat Dawi et al., 2021). Simultaneously, the public’s level of literacy in that topic area would be critical for the correct acquisition of accurate knowledge (Hovland et al., 1953). When these are addressed, direct communication between the government and citizens will reduce a general sense of uncertainty.

Lastly and most importantly, government transparency on the issues at hand must be achieved. Increased overall transparency would prevent various troubles associated with the current spread of disinformation (Kim & Lee, 2012). Through transparency, citizens are given a chance to process and judge the varied information made available by the government, which may decrease unnecessary curiosity or uncertainty concerning topics of interest. Once they develop a firm opinion on the issue, and thanks to their decreased uncertainty, people will not be swayed when they encounter disinformation on the topic. In short, the motivation to spread disinformation can be diminished by eliminating the factors that increase uncertainty in society.

Trust in government was discussed as one of the essential moderators influencing behavioral choices regarding communication of disinformation and as a factor that improves interactions between citizens and the government. Indeed, trust in government was shown to contribute to the adoption of health compliance behaviors recommended by the public health officials amid the COVID-19 outbreak (Clark et al., 2020). On the other hand, distrust can enhance people’s motivation to spread disinformation, as skepticism towards the government biases their judgment on unverified public issues and increases their general feeling of uncertainty (Bordia & DiFonzo, 2005). As solutions to improve trust in government, scholars in the field have emphasized citizen participation, input into government evaluation and political decision making, and transparency of the political and administrative process (Istad, 2020; Kim & Lee, 2012; Kweit & Kweit, 2004). Through active interaction between the government and citizens, encouraged by higher trust in government, miscommunication can be decreased, which could contribute to curtailing the spread of disinformation. In this vein, e-government can assist active interaction by improving service delivery, communication between citizens and the government, and reducing the associated costs (Tolbert & Mossberger, 2006). The Internet can enable more individualized communication with elected officials (e.g., via e-mail), and posting on the Web may force government officials to coordinate procedures, making the government more customer-oriented (Ho, 2002). Additionally, websites can enhance citizens’ voluntary participation in public administration affairs and decision making, while various e-participation applications can be used to increase the transparency of the governmental process (Kim & Lee, 2012). Importantly, perception of security of e-government platforms, which reflects the user’s perceived privacy regarding the use of e-government websites (Papadomichelaki & Mentzas, 2012), should be achieved as it is an essential indicator for believability of the government body (Manoharan et al., 2017). Several scholars have found a positive association between the government website use, e-government satisfaction, and public trust in government (Norris, 2011; Welch et al., 2004). Thus, further development of digital government for the coming era would be crucial for improving public trust in government, which will eventually contribute to reducing the spread of disinformation among the public.

The importance of media-related literacy is justified not only by the level of media exposure but also by the essential role of information in the growth of democracy and active citizenship. It should be acknowledged that regardless of age, digital media acts as a channel for information intake and entertainment and as an agent of socialization (Koltay, 2011). Although almost every citizen is now assumed to be a qualified modern media user, there is no guarantee that every user has an adequate level of media-related literacy, leaving these internet users vulnerable to the risk of disinformation (Guess et al., 2019). This poses a serious challenge to the government as there is still a large proportion of the population that does not seem to meet the sufficient level of media-related literacy, which could potentially be a risk to the operation of a country.

Accordingly, decision makers around the world should address media literacy education at a global level. A new culture should be encouraged, in which the importance of media-related literacy is appreciated. To do so, the cooperation of various stakeholders will be necessary, including governments, schools, non-governmental organizations, media companies, at the local to global levels. Indeed, the recent partnership between UNESCO, European Union, and Twitter to promote media and information literacy is a good example of collaboration (UNESCO, 2020). By disseminating graphics and encouraging the hashtag of #ThinkBeforeSharing, the public was reminded of the importance of media and information literacy skills in navigating through the overwhelming amount of news every day. After reviewing its positive effects, OECD also recommends such an initiative to be replaced by other platforms and relevant stakeholders (OECD, 2020).

For governments to heighten media-related literacy of their citizens, a careful strategy for media literacy education is needed. For instance, an efficient tool for assessing the level of dis/misinformation vulnerability can be constructed to target a susceptible group for customized education to be delivered for effective education. Although numerous researchers are currently trying to identify various factors associated with dis/misinformation belief and spreading behavior, there has yet been an attempt to develop a unified tool to measure citizen’s level of dis/misinformation vulnerability that includes belief, motivational and spreading components. Thus, more academics in the field should dedicate their efforts to promote media-related literacy.

CONCLUSION

Although this generation benefits from advanced digital media technology in many ways, it cannot be said that we are fully equipped to handle the associated challenges such as the problem of disinformation spread. Realizing the limit of interventions that focus on the activity of disinformation publishers to prevent such, numerous scholars have started paying attention to the role of the general public. While these researchers look into various contributors that might cloud people’s judgment on such information or behavior associated with it there has yet to be a more general framework that shows how these contributors might be related to each other throughout the stages of disinformation communication. Therefore, this course of the research, for the first time, attempted to provide a more holistic perspective by laying out the contributors within a single framework. Nevertheless, there is still room for improvement in this research, especially in developing models that are more specific to understanding disinformation spread beyond common information sharing behaviors. We hope that the current work contributes to the literature by providing a foundation to develop a more comprehensible model in the future. Lastly, although it is still premature, we believe that our research will help the understanding of those who are in charge of developing actionable strategies and internationally agreed-upon policies to fight the problem of disinformation spread as well as numerous scholars who are continuously researching into the topic to gain an integrated understanding of the phenomenon.

Disclose statement

We are grateful to the KDI School of Public Policy and Management for providing financial support.

References

-

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236.

[https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211]

- Allport, G. W., & Postman, L. (1947). The psychology of rumor. Henry Holt.

-

Apuke, O. D., & Omar, B. (2021). Fake news and COVID-19: Modelling the predictors of fake news sharing among social media users. Telematics and Informatics, 56, 101475.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101475]

-

Apuke, O. D., & Omar, B. (2020). Fake news proliferation in Nigeria: Consequences, motivations, and prevention through awareness strategies. Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 8(2), 318-327.

[https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2020.8236]

-

Baek, Y. M. (2021). Journalistic values in modern democracy: Balancing power between constitutionalism and populism. Asian Communication Research, 18(1), 8-21.

[https://doi.org/10.20879/acr.2021.18.1.8]

- Banjo, S. (2019, May 19). How digital disinformation sows hate, hurts democracy: QuickTake. Bloomberg Businessweek. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-05-18/facebook-twitter-and-the-digital-disinformation-mess-quicktake

-

Berger, J. (2014). Word of mouth and interpersonal communication: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24(4), 586-607.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2014.05.002]

- Blitz, M. J. (2018). Lies, line drawing, and deep fake news. Oklahoma Law Review, 71(1), 59-116. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/oklrv71&div=9&g_sent=1&casa_token=WKBqMZ6dl8gAAAAA:zhZzaacOylrrc_IEWyEXjy0dXYl1bL2GOno9Bndcx6i1n2W__ZjfQhh3CXsgWUV3Mn0ljVhA&collectionon=journals

-

Bordia, P., & DiFonzo, N. (2004). Problem solving in social interactions on the Internet: Rumor as social cognition. Social Psychology Quarterly, 67(1), 33-49.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250406700105]

-

Bordia, P., & DiFonzo, N. (2005). Psychological motivations in rumor spread. In G. A. Fine, V. Campion-Vincent, & C. Heath (Eds.), Rumor mills: The social impact of rumor and legend (pp. 87-102). Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315128795-10]

-

Bovet, A., & Makse, H. A. (2019). Influence of fake news in Twitter during the 2016 US presidential election. Nature Communications, 10(7), 1-14.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07761-2]

-

Broniatowski, D. A., Jamison, A. M., Qi, S., AlKulaib, L., Chen, T., Benton, A., Quinn, S. C., & Dredze, M. (2018). Weaponized health communication: Twitter bots and Russian trolls amplify the vaccine debate. American Journal of Public Health, 108(10), 1378-1384.

[https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304567]

-

Chang, S. E., Liu, A. Y., & Shen, W. C. (2017). User trust in social networking services: A comparison of Facebook and LinkedIn. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 207-217.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.013]

-

Cheung, C. M. K., & Thadani, D. R. (2012). The impact of electronic word-of-mouth communication: A literature analysis and integrative model. Decision Support Systems, 54(1), 461-470.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.06.008]

-

Cheung, M.-S., Anitsal, M. M., & Anitsal, I. (2007). Revisiting word-of-mouth communications: A cross-national exploration. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 15(3), 235-249.

[https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679150304]

- Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In D. T. Gilvert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 151-192). McGraw-Hill.

-

Clark, C., Davila, A., Regis, M., & Kraus, S. (2020). Predictors of COVID-19 voluntary compliance behaviors: An international investigation. Global Transitions, 2, 76-82.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.glt.2020.06.003]

- Coleman, A. (2020, August 12). “Hundreds dead” because of COVID-19 misinformation. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-53755067

-

Correa, T., Bachmann, I., Hinsley, A. W., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2014). Personality and social media use. In E. Y. Li, S. Loh, C. Evans, & F. Lorenzi (Eds.), Organizations and social networks: Utilizing social media to engage consumers (pp. 41-61). IGI Global.

[https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-4026-9.ch003]

- Dichter, E. (1966). How word-of-mouth advertising works. Harvard Business Review, 44(6), 147-161.

-

DiFonzo, N., & Bordia, P. (1998). A tale of two corporations: Managing uncertainty during organizational change. Human Resource Management, 37(3-4), 295-303.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-050X(199823/24)37:3/4<295::AID-HRM10>3.0.CO;2-3]

-

DiFonzo, N., & Bordia, P. (2007). Rumor, gossip and urban legends. Diogenes, 54(1), 19-35.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0392192107073433]

-

Duffy, A., Tandoc, E., & Ling, R. (2020). Too good to be true, too good not to share: The social utility of fake news. Information, Communication & Society, 23(13), 1965-1979.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1623904]

-

Dunning, D. (2001). On the motives underlying social cognition. In A. Tesser, & N. Schwarz & (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Intraindividual processes (pp. 348-374). Wiley Online Library.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470998519.ch16]

-

Engel, J. F., Kegerreis, R. J., & Blackwell, R. D. (1969). Word-of-mouth communication by the innovator. Journal of Marketing, 33(3), 15-19.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/002224296903300303]

- European Commission. (2008). Council conclusions of 22 May 2008 on a European approach to media literacy in the digital environment. Official Journal of the European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52008XG0606%2801%29

-

Fallis, D. (2008). Toward an epistemology of Wikipedia. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(10), 1662-1674.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20870]

- Fallis, D. (2009, February 28). A conceptual analysis of disinformation. [Paper presentation]. iConference, Chapel Hill, NC, United States. http://hdl.handle.net/2142/15205

-

Fallis, D. (2015). What is disinformation? Library Trends, 63(3), 401-426.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2015.0014]

-

Farid, H. (2008). Digital image forensics. Scientific American, 298(6), 66-71. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26000642?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

[https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0608-66]

- Faris, R., Roberts, H., Etling, B., Bourassa, N., Zuckerman, E., & Benkler, Y. (2017). Partisanship, propaganda, and disinformation: Online media and the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Berkman Klein Research Publication, 2017-6. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3019414

- Fowler, B., Franklin, C., & Hyde, R. (2001). Internet securities fraud: Old trick, new medium. Duke Law & Technology Review. http://dltr.law.duke.edu/2001/02/28/internet-securities-fraud-old-trick-new-medium/

-

Friestad, M., & Wright, P. (1994). The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1), 1-31.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/209380]

-

Guess, A., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. (2019). Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Science Advances, 5(1), eaau4586.

[https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau4586]

-

Güzel, S. A., Özer, G., & Özcan, M. (2019). The effect of the variables of tax justice perception and trust in government on tax compliance: The case of Turkey. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 78, 80-86.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2018.12.006]

-

Heath, C. (1996). Do people prefer to pass along good or bad news? Valence and relevance of news as predictors of transmission propensity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 68(2), 79-94.

[https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1996.0091]

-

Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., Walsh, G., & Gremler, D. D. (2004). Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the Internet? Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(1), 38-52.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.10073]

-

Ho, A. T. (2002). Reinventing local governments and the e-government initiative. Public Administration Review, 62(4), 434-444.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00197]

- Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H. (1953). Communication and persuasion. Yale University Press.

-

Istad, F. (2020). Two-way engagement in public diplomacy: The case of Talk Talk Korea. Asian Communication Research, 17(3), 115-141.

[https://doi.org/10.20879/acr.2020.17.3.115]

-

Jones-Jang, S. M., Mortensen, T., & Liu, J. (2019). Does media literacy help identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other literacies don’t. American Behavioral Scientist. 65(2), 371-388.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219869406]

-

Kim, S., & Lee, J. (2012). E-participation, transparency, and trust in local government. Public Administration Review, 72(6), 819-828.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02593.x]

-

Kim, M., Paek, H.-J., & Hove, T. (2021). Roles of temporal message framing and digital channel type in perception and dissemination of food risk rumors. Asian Communication Research, 18(2), 89-106.

[https://doi.org/10.20879/acr.2021.18.2.89]

- Kimmel, A. J. (2004). A manager's guide to understanding and combatting rumors. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

-

Koc, M., & Barut, E. (2016). Development and validation of new media literacy scale (NMLS) for university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 834-843.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.035]

-

Koltay, T. (2011). The media and the literacies: Media literacy, information literacy, digital literacy. Media, Culture & Society, 33(2), 211-221.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443710393382]

-

Kruger, A. (2017). Ahead of the e-curve in fact checking and verification education: The University of Hong Kong’s cyber news verification lab leads verification education in Asia. Asia Pacific Media Educator, 27(2), 264-281.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1326365X17736579]

-

Kunda, Z. (1999). Social cognition: Making sense of people. MIT press.

[https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/6291.001.0001]

-

Kweit, M. G., & Kweit, R. W. (2004). Citizen participation and citizen evaluation in disaster recovery. The American Review of Public Administration, 34(4), 354-373.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074004268573]

-

Kwon, K. H., Chadha, M., & Pellizzaro, K. (2017). Proximity and terrorism news in social media: A construal-level theoretical approach to networked framing of terrorism in Twitter. Mass Communication and Society, 20(6), 869-894.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2017.1369545]

-

Lai, K., Xiong, X., Jiang, X., Sun, M., & He, L. (2020). Who falls for rumor? Influence of personality traits on false rumor belief. Personality and Individual Differences, 152, 109520.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109520]

-

Lallmahomed, M. Z. I., Lallmahomed, N., & Lallmahomed, G. M. (2017). Factors influencing the adoption of e-government services in Mauritius. Telematics and Informatics, 34(4), 57-72.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.01.003]

-

Lampos, V., Majumder, M. S., Yom-Tov, E., Edelstein, M., Moura, S., Hamada, Y., Rangaka, M. X., McKendry, R. A., & Cox, I. J. (2021). Tracking COVID-19 using online search. NPJ Digital Medicine, 4(17), 1-17.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-021-00384-w]

-

Lee, C. S., & Ma, L. (2012). News sharing in social media: The effect of gratifications and prior experience. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(2), 331-339.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.10.002]

-

Lee, C. S., Ma, L., & Goh, D. H.-L. (2011). Why do people share news in social media? In N. Zhong, V. Callaghan, A. A. Ghorbani, & B. Hu (Eds.), Active media technology (Vol. 6890, pp. 129-140). Springer.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-23620-4_17]

-

Lee, S.-H., Noh, S.-E., & Kim, H.-W. (2013). A mixed methods approach to electronic word-of-mouth in the open-market context. International Journal of Information Management, 33(4), 687-696.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2013.03.002]

-

Ma, L., Lee, C. S., & Goh, D. H. (2013). Understanding news sharing in social media from the diffusion of innovations perspective. 2013 IEEE International Conference on Green Computing and Communications and IEEE Internet of Things and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing, 1013-1020. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6682187

[https://doi.org/10.1109/GreenCom-iThings-CPSCom.2013.173]

-

Manoharan, A. P., Zheng, Y., & Melitski, J. (2017). Global comparative municipal e-gov ernance: Factors and trends. International Review of Public Admini stration, 22(1), 14-31.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2017.1292031]

- Marwick, A., & Lewis, R. (2017). Media manipulation and disinformation online. Data & Society. https://datasociety.net/pubs/oh/DataAndSociety_MediaManipulationAndDisinformationOnline.pdf

-

Mat Dawi, N., Namazi, H., Hwang, H. J., Ismail, S., Maresova, P., & Krejcar, O. (2021). Attitude toward protective behavior engagement during COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia: The role of e-government and social media. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 1-8.

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.609716]

- McLennan, D., & Miles, J. (2018, March 21). A once unimaginable scenario: No more newspapers - The Washington Post. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/theworldpost/wp/2018/03/21/newspapers/?utm_term=.2e914555f82e

- Norris, P. (2011). Democratic deficit: Critical citizens revisited. Cambridge University Press.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2020). Combatting COVID-19 disinformation on online platforms (OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19)). https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/combatting-covid-19-disinformation-on-online-platforms-d854ec48/

-

Papadomichelaki, X., & Mentzas, G. (2012). e-GovQual: A multiple-item scale for assessing e-government service quality. Government Information Quarterly, 29(1), 98-109.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2011.08.011]

-

Park, Y. J., Chung, J. E., & Shin, D. H. (2018). The structuration of digital ecosystem, privacy, and big data intelligence. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(10), 1319-1337.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218787863]

-

Park, H., & Lee, T. (2018). Adoption of e-government applications for public health risk communication: Government trust and social media competence as primary drivers. Journal of Health Communication, 23(8), 712-723.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2018.1511013]

-

Phillips, W. (2015). This is why we can’t have nice things: Mapping the relationship between online trolling and mainstream culture. The MIT Press.

[https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10288.001.0001]

-

Price, L. L., Feick, L. F., & Guskey, A. (1995). Everyday market helping behavior. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 14(2), 255-266.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/074391569501400207]

-

Roozenbeek, J., & van der Linden, S. (2019). Fake news game confers psychological resistance against online misinformation. Palgrave Communications, 5(65), 1-10.

[https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0279-9]

-

Rosnow, R. L. (1991). Inside rumor: A personal journey. American Psychologist, 46(5), 484-496.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.5.484]

- Rosnow, R. L., & Fine, G. A. (1976). Rumor and gossip: The social psychology of hearsay. Elsevier.

-

Schachter, S., & Burdick, H. (1955). A field experiment on rumor transmission and distortion. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 50(3), 363-371.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/h0044855]

-

Schuetz, S. W., Sykes, T. A., & Venkatesh, V. (2021). Combating COVID-19 fake news on social media through fact checking: Antecedents and consequences. European Journal of Information Systems, 30(4), 376-388.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2021.1895682]

- Shen, W., Huang, J., & Li, D. (2016). The research of motivation for word-of-mouth: Based on the self-determination theory. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research, 10(2), 75-84. https://www.jbrmr.com/cdn/article_file/i-23_c-217.pdf

-

Stevens, L. E., & Fiske, S. T. (1995). Motivation and cognition in social life: A social survival perspective. Social Cognition, 13(3), 189-214.

[https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.1995.13.3.189]

- Sundaram, D. S., Mitra, K., & Webster, C. (1998). Word-of-mouth communications: A motivational analysis. Advances in Consumer Research, 25, 527-531. https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/8208/volumes/v25/N

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), Psychology of Intergroup Relations (pp. 7-24) Nelson-Hall Publishers.

-

Tesser, A., & Rosen, S. (1975). The reluctance to transmit bad news. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 8, 193-232.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60251-8]

-

Thompson, F. M., Tuzovic, S., & Braun, C. (2019). Trustmarks: Strategies for exploiting their full potential in e-commerce. Business Horizons, 62(2), 237-247.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2018.09.004]

- Thompson, N., Wang, X., & Daya, P. (2019). Determinants of news sharing behavior on social media. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 1-9.

-

Tolbert, C. J., & Mossberger, K. (2006). The effects of e-government on trust and confidence in government. Public Administration Review, 66(3), 354-369.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00594.x]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2020, April 21). European social media campaign to address disinformation on Covid-19 & #ThinkBeforeSharing. UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/news/european-socia-media-campaign-address-disinformation-covid-19-thinkbeforesharing

-

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146-1151.

[https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559]

-

Walker, C. J., & Blaine, B. (1991). The virulence of dread rumors: A field experiment. Language & Communication, 11(4), 291-297.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0271-5309(91)90033-R]

-

Wang, T., Yeh, R. K.-J., Chen, C., & Tsydypov, Z. (2016). What drives electronic word-of-mouth on social networking sites? Perspectives of social capi tal and self-determination. Telematics and Informatics, 33(4), 1034-1047.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.03.005]

- Web Desk. (2020, April 5). Amid the coronavirus pandemic, a fake news ‘infodemic.’ The Week. https://www.theweek.in/news/india/2020/04/05/amid-the-coronavirus-pandemic-fake-news-infodemic.html

-

Weenig, M. W. H., Groenenboom, A. C. W. J., & Wilke, H. A. M. (2001). Bad news transmission as a function of the definitiveness of consequences and the relationship between communicator and recipient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(3), 449-461.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.3.449]

-

Welch, E. W., Hinnant, C. C., & Moon, M. J. (2004). Linking citizen satisfaction with e-government and trust in government. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 15(3), 371-391.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mui021]

-

West, D. M. (2004). E-government and the transformation of service delivery and citizen attitudes. Public Administration Review, 64(1), 15-27.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00343.x]

-

Yum, J. Y., & Jeong, S. H. (2019). Predictors of fake news exposure and sharing: Personality, new media literacy, and motives. Korean Journal of Journalism & Communication Studies, 63(1), 7-45.

[https://doi.org/10.20879/kjjcs.2019.63.1.001]

-

Zarocostas, J. (2020). How to fight an infodemic. The Lancet, 395(10225), 676.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X]