Can Chinese Pastoral Videos be Effective for Promoting Foreign Viewers’ Travel and Word-of-Mouth Intention? Exploring Characteristics of Chinese Influencer, Attributes of Content, and the Mediating Role of Parasocial Interaction

Copyright ⓒ 2024 by the Korean Society for Journalism and Communication Studies

Abstract

This study investigates how the attributes of Chinese Pastoral Videos (CPVs) content and the characteristics of CPVs influencer affect viewers through parasocial interaction (PSI) on intention to visit China and intention of Word of Mouth (WoM) about CPVs. Results from an online survey with a US sample (N = 405) revealed that physical attractiveness and familiarity of CPVs influencer, along with informativeness of CPVs content, were positively associated with travel intention. Only trustworthiness of CPVs influencer was positively associated with WoM intention. Second, physical attractiveness, trustworthiness, and familiarity of CPVs influencer, along with technicality of CPVs content, were positively associated with behavioral PSI. Informativeness, technicality, and entertainment of CPVs content, along with physical attractiveness and familiarity of CPVs influencer, were positively associated with cognitive PSI. Third, cognitive and behavioral PSI were positively related to travel intention and WoM intention. Finally, cognitive PSI significantly mediated the relationships among characteristics of CPVs influencer, attributes of CPVs content, travel intention and WoM intention. Meanwhile, behavioral PSI significantly mediated the relationships among characteristics of CPVs influencer, technicality of CPVs content, travel intention and WoM intention. This study highlights the potential effectiveness of Chinese pastoral videos in promoting cultural export, including cultural diffusion and visits to China.

Keywords:

Chinese pastoral videos, cultural export, characteristics of influencer, attributes of content, parasocial interaction, behavioral intentionOver the past few decades, user-generated content has exploded on social media platforms, driven by the prominence of video-sharing platforms. The prevalence of user-generated content has provided regular people with opportunities to showcase their life stories and personal expertise, attracting large followers and fostering engagement (Moon, 2023; Wei et al., 2024). User-generated content now encompasses various topics including fitness, fashion, cosmetics and medicine, continuously evolving to meet the needs of viewers. Recently, Chinese Pastoral Videos (CPVs), created by residents of rural Chinese areas, have gained significant popularity on video-sharing platforms with their unique style. CPVs typically depict the rural lifestyles and activities of Chinese villages such as farming, cooking, and handcrafting (Guo & Abidin, 2021). They portray a ‘pre-industrial seemingly’ utopia infused with elements of traditional Chinese culture in which viewers engage in a ritual of viewing, disussing and sharing with others (Li & Adnan, 2023a).

In recent years, the influence of CPVs has been growing in Chinese society. According to a TikTok report (2023), the number of CPVs exceeded 4.69 billion, and the total number of views reached a staggering 2.39 trillion in mainland China by 2022. Many local governments have leveraged CPVs to enhance local cultural visibility and promote local merchandise to revive the local economy (Liang, 2022). Furthermore, CPVs have attracted significant attention overseas. On YouTube, channels dedicated to CPVs have amassed over 30 million subscribers, most of whom are non- Chinese (Liang, 2023). Recognized for distinct national hue and cultural identity, researchers argue that CPVs may serve as a type of culture export, particularly in enchancing interest and image for a travel destination (Li & Adnan, 2023a; X. Zhang et al., 2021). Indeed, CPVs offer a unique discourse, enabling viewers from diverse cultural backgrounds to appreciate Chinese traditional culture, potentially fostering favorable impressions of China and reducing existing stereotypes (Li, 2019; Zhang, 2022).

While CPVs have demonstrated significant cultural effects, previous studies were conducted to find marketing effects of CPVs with consumers’ brand attitude, Word-of-Mouth (WoM), and purchase intentions (Li & Adnan, 2023a; Li et al., 2023; Wang, 2022; Zhang, 2022). However, relatively little is studied about mechanisms of CPVs in cultural promotion context. Given the extensive vieweship, and potential cultural impact, it seems crucial to understand the influence of CPVs from the perspective of cultural export. To address this gap, this study investigated how CPVs function as a cultural carrier that promotes interests in China. Specifically, this study examined whether vieweing CPVs shown by influencers can be associated for foreign audiences to shape their intention to visit and spread words about China.

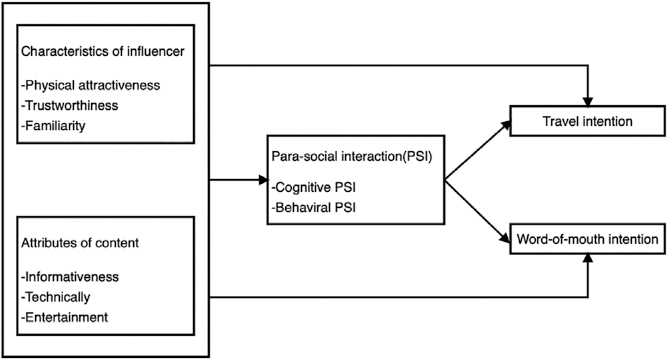

According to the communication-persuasion matrix (McGuire, 2001), two major components - messenger and source - determine its effectiveness in communication. Studies on influencer marketing have focused either on creator/ influencer-based factors or content-based factors (Kanaveedu & Kalapurackal, 2022; Kim, 2022). This study dealt with the effects of factors with the messenger, CPVs influencer and the source, CPVs content. It examined how characteristics of CPVs influencer (e.g. physical attractiveness, trustworthiness, and familiarity) and attributes of CPVs content (e.g. informativeness, technicality, and entertainment) served as determinants affecting audiences’ behavioral intentions, including intentions to visit China and to engage in Word-of-Mouth (WoM) about CPVs.

Given the real-time live communication between CPVs and viewers, the interaction between these two parties is crucial for understanding the influence of CPVs. The concept of parasocial interaction (PSI) enables researchers to understand how audiences build relationships with media personalities and how these interactions influence viewing behaviors (Kim, 2022). Previous studies (Jin et al., 2018; Kim, 2022; Shin & Han, 2019) have demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive and behavioral aspects in investigating PSI’s influence on viewers’ perception and behavior. To understand the impact of CPVs on cultural outcomes, this study also employed cognitive and behavioral dimensions of PSI to investigate their mediating effects between CPVs and viewers’ behavioral intentions. This study examined whether the characteristics of CPVs influencer and attributes of CPVs content affected PSI. Furthermore, it explored whether PSI between influencers and viewers affected viewers’ behavioral intentions. Finally, this study postulated a causal relationship whereby the characteristics of CPVs influencer and the attributes of CPVs content affected para-social interaction, which in turn influenced viewers’ behavioral intentions.

Chinese Pastoral Videos as a Cultural Export

With the advancement of communication technologies, the widespread use of social media has provided rural Chinese communities with increased visibility and voice. Chinese pastoral videos (CPVs) seems to embody Virno’s (2004) concepts of “the social factory” and “immaterial labor”, where social productions are no longer confined to factory or office, but instead produce immaterial goods such as service, cultural product, knowledge, or communication. CPVs are praised for depicting rural life, known as “yuanshengtai” in Chinese – a concept conceptualized as “unpolluted native” in Western anthropology and commonly used to represent a type of “untainted original and harmonious relationship with the natural environment” (Kendall, 2019). In essence, CPVs represent a combination of bucolic tranquility and preindustrial charm. By showcasing rudimentary farming, animal husbandry, rural cooking, and other mundane aspects of daily living, CPVs enable viewers from various cultural backgrounds to directly observe daily life in rural China (Guo & Abidin, 2021). With their aesthetically appealing visuals, leisurely pace, and exotic rural settings, CPVs effectively bridge language and cultural barriers. Unconstrained by cultural and historical contexts, CPVs may appeal to individuals across a wide range of linguistic or cultural backgrounds, political ideologies and personal interests.

Recently, China has engaged in dialogue with the global community, aiming to share its scenic beauty and rich cultural heritage. Also proliferation of CPVs on global media platforms has broadened opportunities for cultural export. By showcasing cultural diversity grounded in cultural identity, CPVs seek to foster a common experience between China and the global community (Yu & Zhang, 2021). As a channel that narrates rural Chinese life stories, CPVs effectively expand the scope of national cultural export (Li & Adnan, 2023b). The Chinese state media have endorsed CPVs as a symbol of cultural export and an intercultural communication channel for sharing stories about China (Zhang, 2022). While previous studies on influencer marketing established impacts of exposure through influencer-generated content in promoting specific, targeted brands and products, this study concerned whether exposure to cultural content such as CPVs, which was not exactly intended for tourism of China, and interactions with influencing creators could extend to viewers’ intentions to visit and talk about China amongst foreign audience.

Factors Affecting Intentions of Visiting China and WoM about CPVs

Social media influencers, as a new type of thirdparty endorsers, utilize their blogs, tweets, and other video tools to influence consumers’ decision-making process (Freberg et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2021). Compared to celebrities or public figures who are well-known through traditional media, social media influencers are often “regular people” who have become online celebrities by creating and posting content on social media. These influencers are frequently approached by brands for product endorsements or reviews (Godey et al., 2016; Nandagiri & Philip, 2018).

Studies on social media influencers have primarily focused on the crucial role of influencer credibility in marketing (Cunningham & Bright, 2012; Kanaveedu & Kalapurackal, 2022; Lee & Koo, 2015). In advertising and marketing research, endorsers (i.e. influencer) generally function as message sources in the persuasion process (Lou & Yuan, 2019). A large body of studies have verified that credibility of the message source influences the effectiveness of persuasive messages and have identified three components of source credibility: attractiveness, trustworthiness and familiarity (Hovland & Weiss, 1951; Hovland et al., 1953; Munnukka et al., 2016; Ohanian, 1990). Studies on the endorsement effects of influencers have also shown that these components of influencer credibility were significant factors associated with consumers’ purchase decision-making toward specific brands (Lou & Yuan, 2019; Martensen et al., 2018; Rubin & Step, 2000). Drawing from empirical evidence, this study investigated the impact of CPVs influencer from three components.

First, physical attractiveness is a crucial factor in persuasion research and is typically defined as attractiveness of an individual’s appearance. It is regarded as a crucial characteristic, as it can be visually perceived by viewers (Rubin & Step, 2000). Many studies have demonstrated that physical attractiveness exerts positive effects on individual’s attitude or behavioral intention (Berscheid & Walster, 1974; Lee & Watkins, 2016; Liu et al., 2020). In this study, physical attractiveness is particularly emphasized with CPVs influencer because their contents usually are non-verbal and focus on showcasing personal characteristics. Accordingly, viewers become more attentive to their appearances than social attractiveness such a as conversation skills and personal etiquette.

Second, trustworthiness is viewed as the propensity to rely on a peer with one has confidence (Moorman et al., 1992). The trustworthiness of an influencer is perceived when viewers feel that the influencer is reliable and honest (Munnukka et al., 2016; Ohanian, 1990). According to previous studies (Amelina & Zhu, 2016; Chekima et al., 2020; Jin et al., 2018; Lou & Yuan, 2019; Wiedmann & von Mettenheim, 2021), the trustworthiness of an influencer was positively related to viewers’ attitude about brand and purchase intention. As a presenters of a simple, rustic lifestyle and authentic scenes of rural Chinese villages, trustworthiness is considered essential characteristics of the CPVs influencer.

Third, familiarity is regarded as an essential factor in influencer-related research. Consumers’ past exposure or association with a product or a brand can be related to familiarity (Alba & Hutchinson, 1987; Martensen et al., 2018). Familiarity reflects a sense of closeness an influencer is to consumers (Supriyanto et al., 2023) and gives a level of comfort to receivers about the sender (Martensen et al., 2018). When viewers feel a sense of familiarity with an influencer, they are more likely to embrace their opinions and possibly change their attitudes (Martensen et al., 2018). Studies also indicated a positive relationship between influencer’s familiarity and individuals’ behavioral intention (Fei & Lee, 2021; Lee et al., 2020; Torres et al., 2019). CPVs influencer usually appear in real-life settings alongside friends and family in videos, conveying a sense of closeness to viewers. Therefore, familiarity is proposed as one of the characteristics of CPVs influencer in this study.

Based on previous research, the following hypothesis was proposed:

- H1. The characteristics of CPVs influencer (physical attractiveness, trustworthiness, and familiarity) will be positively associated with viewers’ intentions to visit China and WoM about CPVs.

Over the past decade, a variety of social media platforms have been utilized by ordinary people to generate and distribute content such as videos, images, audio, and text. User-generated content is actively ingested and disseminated by the public, attributed to its potential for interactivity and minimal cost. Discussing the advertising value of content generated by influencers, Lou and Yuan (2019) noted that social media updates (i.e., blogs and posts) produced by influencers in their areas of expertise encompass informational and entertainment values to their subscribers. For example, beauty influencers often show how they apply makeup products and share their experience in a particular manner. Influencers also show personal qualities such as wits and charm in their posts, typically providing an enjoyable experience for their followers. Previous studies have demonstrated that informativeness and entertainment of influencer-generated content positively predicted consumers’ attitude and purchase intention (Hughes et al., 2019; Lou & Yuan, 2019; Shin & Han, 2019). In addition, with the explosive growth of video platforms, consumers’ demand for high-quality posts has increased. Given viewers’ increased visual standards, technical quality of content becomes an important consideration for influencer-generated content in terms of affecting consumer purchase decision-making process. According to Aleti et al. (2019), visual congruence of the posts increases engament with influencer content and is related with followers’ purchase intentions. Thus, this study explored the influence of CPVs content in terms of three attributes: informativeness, entertainment, and technicality.

First, informativeness is defined as the degree to which people perceive the information they receive about a product or service as applicable (Arviansyah et al., 2018). Previous studies found that online videos are primarily viewed for their informational value (Choi & Behm-Morawitz, 2017; Dehghani et al., 2016). Individuals were more likely to respond to content if they perceived it to be informative, and the informativeness of content was positively related to viewing intentions and perceived satisfaction (Cappella & Li, 2023; Kitirattarkarn et al., 2019). Given that the majority of CPVs focus on introducing the Chinese traditional culture and various daily activities in rural villages, the content can serve as information about the Chinese rural and traditional culture for interested viewers.

Second, entertainment is defined as the extent to which a person perceives delight or enjoyment through a particular content (Shin & Han, 2019). The entertainment factor was found to positively motivate the use of content on social media (Knoll & Proksch, 2017; Luo et al., 2011). Similarly, those who used media content as a source of entertainment sought emotional relaxation and influenced their psychological state by viewing these contents (Stoeckl et al., 2007; Verhagen & van Dolen, 2011). A positive relationship between the entertainment of short video and individuals behavioral intentions were found in several studies (Choi & Jung, 2018; Kim et al., 2021; Lee & Hwang, 2018; Park & Lee, 2021). CPVs typically feature novel Chinese things including distinctive handicrafts, and authentic culinary recipes that viewers from other cultures have never seen before. This may lead viewers to perceive the content as entertaining and exciting. Perceived entertainment value in CPVs is considered a significant factor in the present study.

Third, a common use of smartphones enables individuals to easily shoot, edit, and upload content online, providing viewers with a comprehensive understanding of visual information in various fields such as subtitles, lighting, photography props, and photography equipment (Byun, 2018). Moreover, visual elements such as layout, color, and illumination become significant factors influence viewers’ immersion and response (Kim et al., 2012). Visual characteristics (editing abilities, typefaces, emojis) positively related to viewers’ responses to products (Kim et al., 2012; Valentini et al., 2018). Similarly, technicality (e.g., technical editing, lighting, equipment, etc.) as a means for visual effect influences individuals’ behavioral intention (Silk et al., 2021).

Based on previous backgrounds, the following hypothesis was proposed:

- H2. Th e at t r i butes o f CPVs content (informativeness, entertainment, and technicality) will be positively associated with users’ intentions to visit China and WoM about CPVs.

Horton and Wohl (1956) introduced the concept of para-social interaction (PSI) to characterize individuals’ responses to media personalities while consuming television programs. Specifically, PSI is the relationship a spectator develops with a performer, with perceived intimacy akin to ‘real’ interpersonal relationships (Dibble et al., 2016). The nature of this relationship is a simulated interaction that viewers gradually develop with media characters over time, and viewers may not be aware of its existence or influence (Kelman, 1958). Considering the interactive nature and participatory culture of social media, PSI with social media influencers could happen more complex ways. For example, when an influencer conducts a live streaming, users can watch the live and communicate with the influencer and other users by leaving comments, conversing with each other and even buying a product on site.

The conceptualization of PSI has evolved as many studies have been conducted, and numerous measures have emerged for accurately assessing parasocial interaction (Dibble et al., 2016). PSI-process scales developed by Schramm and Hartmann (2008) have been considered universal and valid measurements across various contexts (Schramm & Wirth, 2010). They posited that PSI could be conceptualized as parasocial processing, regarded as a type of interpersonal involvement (Hartmann, 2008). Based on the Two-Level Model of PSI (Hartmann et al., 2004; Klimmt et al., 2013), they further refined the PSI-process scale comprising of three dimensions: cognitive, affective and behavioral. This scale multidimensionally measures intensity and the breadth of PSI and allows for comparisons of each dimensions (Dibble et al., 2016). The dimensions were also applied either in a whole or in part, depending on focus of specific parasocial process (Schramm & Hartmann, 2008; Schramm & Wirth, 2010;). At present, numerous studies have utilized selected parts of PSI-process scale to assess interactions between viewers and media personalities in different setting/contexts (Dibble et al., 2016; Rasmussen, 2018; Schramm & Wirth, 2010; Shin & Han, 2019). Studies that examined parasocial interaction with social media influencer employed cognitive and behavioral dimension of PSI (Rasmussen, 2018; Shin & Han, 2019), and the current study accordingly based the selected dimensions of PSI: cognitive and behavioral.

Lee and Watkins (2016) showed that PSI was affected by influencer’ physical attractiveness and familiarity. Shin and Han (2019) found that the technicality and entertainment of influencer’s Youtube content were positively related to PSI. A positive relationship between PSI and consumers’ decision-making process was also found. Hwang and Zhang (2018) showed that PSI was positively related to viewers’ purchase intention of products recommended by influencer and to electronic WoM intention for influencer’ advertising. In predicting a continuous use of content, Sokolova and Perez (2021) showed that PSI positively affected individuals’ intention to watch fitnessrelated YouTube videos continuously.

Based on previous studies, the following hypotheses were proposed:

- H3. The characteristics of CPVs influencer will be positively associated with cognitive and behavioral PSI.

- H4. The attributes of CPVs content will be positively associated with cognitive and behavioral PSI.

- H5. Cognitive and behavioral PSI will be positively associated with users’ intentions to visit China and WoM about CPVs.

However, several studies (Hwang & Zhang, 2018; Kim et al., 2021; Manchanda et al., 2022; Shin & Han, 2019) have shown that a mediating role of PSI, indicating that a relationship with social media influencers could influence subsequent behaviors. This implies that communication with social media influencers can lead not only to generating desires for a specific product or service but also to transferring to other related behavioral intentions (Kim, 2022).

Based on previous studies, the following hypotheses were proposed:

- H6. Cognitive and behavioral PSI will mediate the relationship between the characteristics of CPVs influencer and users’ intentions to visit China and WoM about CPVs.

- H7. Cognitive and behavioral PSI will mediate the relationship between the attributes of CPVs content and users’ intentions to visit China and WoM about CPVs.

Drawing from the literature reviewed above, the research model of this study is posited and shown in Figure 1.

METHOD

Data Collection

To familiarize participants with the Chinese pastoral videos, two Chinese pastoral channels on YouTube, Liziqi and Dianxi Xiaoge, were selected. Two channels were chosen because they are the most popular YouTube channels depicting the Chinese pastoral content, with 19.5 million and 6.91 million followers, respectively. Participants were presented with two videos with the highest click-through rates from each channel for about 120 seconds (e.g. Liziqi: 128 million and Dianxi Xiaoge: 44 million rates). To recruit participants, an invitation with a link was randomly sent to potential participants via an online survey platform. Specially, all participants from this study read a standard consent form and informed consent was obtained at the beginning of the online survey. After agreeing to participate, respondents were instructed to view the two videos and complete questionnaires about CPVs. From May 4, 2022, to May 15, 2022, a total of 405 participants residing in the United States were recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). As compensation, the researcher paid $3 per response to the platform for collecting data. After eliminating duplicate or incomplete responses, the total number of valid samples was 396. The average age of respondents was 40.2 years (SD = 3.74), and 64.6% were male. Most respondents had a bachelor’s degree or higher (77.5%), and a quarter had a monthly income between $3000 and $3999 (26.0%).

Measurement

In this study, all questions were rated on a sevenpoint Likert scale. Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with the given statements on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Independent Variable

Physical attractiveness is defined as the degree to which the appearance features elicit praise or happiness from others and is regarded as the degree of elegance, sexiness, and beauty (Lee et al., 2020). It was measured by items including “The appearance of influencer in the Chinese pastoral videos (CPVs) is average or above average,” “CPVs influencer is attractive,” and “CPVs influencer has an oriental beauty” (M = 5.46, SD = 1.31, Cronbach’s α = .84).

Trustworthiness refers to the degree of confidence in and acceptance of that individual (Chekima et al., 2020; Lou & Yuan, 2019), measured by items including “I believe that the influencer in Chinese pastoral videos (CPVs) is reliable,” “I believe that the CPVs influencer is genuine,” and “CPVs influencer possesses a sense of authenticity” (M = 5.20, SD = 1.36, α = .86).

Familiarity was defined as a feeling of closeness between influencer and viewers (Torres et al., 2019), measured by items including “I feel that the influencer in Chinese pastoral videos (CPVs) is near to me,” “CPVs influencer makes me feel at ease,” and “CPVs influencer gives me a warm sensation” (M = 5.10, SD = 1.32, α = .82).

Informativeness was defined as the degree to which the Chinese pastoral video is perceived as having informational value by viewers (Choi & Jung, 2018; Shin & Han, 2019). It was measured by items including “Chinese pastoral videos (CPVs) provides valuable information,” “CPVs provides information that is useful for understanding the Chinese culture,” and “CPVs provides a multitude of information about China” (M = 4.98, SD = 1.25, α = .76).

Entertainment referred to the viewer’s perception of enjoyment the content has offered (Kim et al., 2012), measured by items including “Chinese rural videos (CPVs) is unique and I have never seen them before,” “By watching novelty ideas and scenery, I feel enjoyable,” “Watching the landscape of the Chinese countryside makes me enjoyable” (M = 5.27, SD = 1.27, α = .88).

Technicality was the degree to which superior editing skills and sophisticated apparatus are utilized (Shin & Han, 2019), measured by items including “Chinese pastoral videos (CPVs) uses lighting tools and decorations to enhance video quality,” “To enhance the visual effect, CPVs uses traditional music, precise subtitles, and illustrations” and “CPVs editors are quite skilled” (M = 5.23, SD = 1.30, α = .84).

Dependent Variable

Intention of visiting China refers to the desire to travel to China after viewing CPVs (Y. Zhang et al., 2021), measured by items including “I anticipate traveling to China in the future,” “If everything goes according to plan, I will plan to travel to China in the future”, and “I am willing to travel to China in the future” (M = 5.33, SD = 1.21, α = .82).

Intention of WoM about CPVs was defined as the viewers’ intention to share relevant information about CPVs with others (Mikalef et al., 2013), measured by items including “I would recommend the Chinese pastoral videos (CPVs) influencers’ channel to others,” “I would discuss the CPVs content with others in everyday life,” and “I would like to share the CPVs content on social media” (M = 5.25, SD = 1.29, α = .86).

Mediating Variable

The concept of para-social interaction (PSI) has been defined as the relationship between a spectator and a performer in which there is perceived intimacy as in a ‘real’ interpersonal relationship (Dibble et al., 2016; Horton & Wohl, 1956). This study treated PSI as the viewers’ cognitive and behavioral responses to CPVs influencer.

The measurement of CPSI was adopted from previous studies (Schramm & Hartmann, 2008; Shin & Han, 2019). Respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with the following items: “When I watch the Chinese pastoral videos (CPVs), I feel like a member of her group,” “ I consider the CPVs influencer to be an old acquaintance” and “The CPVs influencer makes me feel at ease, as if I were with my peers” (M = 4.86, SD = 1.40, α = .85).

The measurement of BPSI was adopted from previous studies (Schramm & Hartmann, 2008; Shin & Han, 2019). Respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with the following items: “If there were news about the Chinese pastoral videos (CPVs) influencer in a newspaper or website, I would read it,” “If the CPVs influencer appeared on another YouTube channel, I would view it” and “I would like to meet the Chinese rural video influencer in person” (M = 5.20, SD = 1.20, α = .79).

Control Variable

Prevous communication and marketing research has demonstrated that attitude toward specific brands significantly affect consumers’ purchase decision-making process (Lee et al., 2020). As the primary objective of the current study was to investigate relationships among related factors with CPVs, para-social interaction with users’ behavioral intentions, attitude toward the Chinese culture was placed as a control variable in the model testing. Attitude toward the Chinese culture refers to viewers’ positive or negative reaction to the Chinese culture (Lee et al., 2020), measured by items including “I am interested in the Chinese culture,” “I have a favorable attitude toward the Chinese culture” and “I prefer the Chinese culture over cultures of other countries” (M = 5.26, SD = 1.19, α = .79). Additionally, participants’ demographic factors such as age and gender were also included as a control variable in this study (Lou & Yuan, 2019).

RESULTS

Model Testing

SPSS Amos 27.0 was used to evaluate the proposed research hypotheses, using path analysis techniques based on structural equation modeling (SEM). The analyses were conducted using 5,000 bootstrap samples with 95% confidence intervals. First, the validity of the instruments was examined using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Each construct’s Cronbach’s alpha exceeded the minimum requirement of 0.7 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The model’s fit in this study was within acceptable limits (CMIN / d.f. = 1.13, p < .001; CFI = .98, TLI = .97; RMSEA = .03; SRMR = .08). Secondly, factor loading, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR) were used to evaluate convergent validity. These thresholds are met by minimum requirements for factor loading (most > 0.5), AVE (most > 0.5), and CR (most > 0.7), respectively (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Finally, discriminant validity holds if the square root of the AVE is greater than the associations between the given and other constructs for each latent construct (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Discriminant validity of the model’s holds true for off-diagonal entries (see Appendix 1).

Direct Effects

SEM (Structural Equation Modeling) was used to investigate the research hypotheses. Participants’ attitudes toward the Chinese culture and demographic variables (i.e., age, gender) were employed as control variables. Analyses showed an excellent model fit, CMIN / d.f. = 1.64, p < .001; CFI = .96, TLI = .95; RMSEA = .04; SRMR = .01 (see Figure 2). The results of direct effects are summarized in Table 1. Familiarity (β = .15, p < .001) and physical attractiveness (β = .17, p < .001) of CPVs influencer were positively related to the intention to visit China. H1a was partially supported. In contrast, only trustworthiness (β = .17, p < .001) of CPVs influencer was positively associated with intention of WoM about CPVs. H1b was partially supported. Regarding attributes of CPVs content, informativeness (β = .20, p < .001) of CPVs content was positively related to intention to visit China. H2a was partially supported. However, no statistically significant relationship were found between attributes of CPVs content and intention of WoM about CPVs, thus, H2b was not supported.

Results of Structural Equation Modeling AnalysisNote. Entries are standardized coefficients with standard errors. The proposed model fulfills the model-fit criteria: CMIN / df = 1.69 (p <.00), comparative fit index (CFI) = .96, goodness-of-fit-index (GFI) = 1.00, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .04 (p < .001), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .01, and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = .95.*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Furthermore, CPVs influencer’s physical attractiveness (β = .19, p < .001) and familiarity (β = .16, p = .002) were positively related to cognitive PSI (CPSI). H3a was partially supported. Physical attractiveness (β = .25, p < .001), trustworthiness (β = .13, p = .023) and familiarity (β = .16, p = .009) of CPVs influencer were positively related to Behavioral PSI (BPSI). H3b were supported. Informativeness (β = .30, p < .001), technicality (β = .25, p < .001) and entertainment (β = .20, p < .001) of CPVs content were positively related to CPSI. H4a was supported. However, only technicality of CPVs content (β = .31, p < .001) was positively related to BPSI, thus, H4b was partially supported. Both CPSI and BPSI were positively related to intention to visit China (βTI = .37, p = .032; βWOMI = .31, p < .001) and intention of WoM about CPVs (βTI = .37, p = .032; βWOMI = .32, p < .001). H5a and H5b were supported.

Indirect Effects

The results of indirect effects are summarized in Table 2. With respect to cognitive PSI, results indicated that CPSI played a significant mediating role in the relationship between characteristics of CPVs influencer (i.e. physical attractiveness, β = .07, p = .013, 95% CI [.02, .14]; trustworthiness, β = .09, p = .004, 95% CI [.04, .22]; familiarity, β = .06, p = .012, 95% CI [.02, .13]) and intention to visit China. A significant mediating effect of CPSI was also shown in the relationship between characteristics of CPVs influencer (i.e. physical attractiveness, β = .03, p = .006, 95% CI [.00, .10]; trustworthiness, β = .07, p = .038, 95% CI [.02, .17]; familiarity, β = .11, p = .005, 95% CI [.04, .31]) and intention of WoM. H6a was supported. In addition, CPSI also revealed a significant mediating effect in the relationship between the attributes of CPVs content (i.e. informativeness, β = .08, p = .012, 95% CI [.02, .15]; technicality, β = .10, p = .009, 95% CI [.03, .21]; entertainment, β = .05, p = .011, 95% CI [.01, .13]) and intention to visit China. A full mediation effect of CPSI in the relationship between the attributes of CPVs content (i.e. informativeness (β = .04, p = .004, 95% CI [.01, .09]), technicality (β = .02, p = .004, 95% CI [.01, .08]) and entertainment (β = .01, p = .003, 95% CI [.02, .08]) and intention of WoM was discovered. Thus, H7a were supported.

Regarding behavioral PSI, results showed that BPSI played a significant mediating effect in the relationship between characteristics of CPVs influencer (i.e., physical attractiveness, β = .06, p = .013, 95% CI [.02, .13]; trustworthiness, β = .07, p = .010, 95% CI [.03, .14]; familiarity, β = .09, p = .021, 95% CI [.03, .27]) and intention to visit China. BPSI also showed a significant mediating effect in the relationship between characteristics of CPVs influencer (i.e. physical attractiveness, β = .11, p < .01, 95% CI [.04, .28]; trustworthiness, β = .03, p = .002, 95% CI [.00, .10]; familiarity, β = .07, p = .015, 95% CI [.02, .19]) and intention of WoM. Thus, H6b was supported. BPSI showed a full mediating effect in the relationship between technicality of CPVs content, intention to visit China (β = .08, p = .010, 95% CI [.03, .14]) and intention of WoM (β = .04, p = .005, 95% CI [.01, .09]). Thus, H7b was partially supported.

DISCUSSION

The present study began with a question of whether culturally foreign content on global social media platforms could affect individuals from different cultures in their perceptions and behaviors. We noted that the Chinese pastoral videos, which showcase traditional and exotic lifestyles of rural areas, have garnered substantial viewership and subscribers from people across many different cultural backgrounds. Consequently, both content attributes and influencer characteristics were examined in relation to viewers’ intention to visit China and to spread word about these CPVs. We considered parasocial interaction with CPVs influencer as a mediating variable, linking perceptions of content and influencers to behavioral intentions. The results revealed that viewing CPVs played a significant role in viewers’ behavioral intentions among non-Chinese respondents.

The following is a summary of the findings: Physical attractiveness and familiarity of CPVs influencer were positively associated with the intention to visit China. CPVs influencer who appeared attractive in traditional Chinese outfits and exuded a sense of closeness lead foreign viewers to enhance travel intention. This result indicated that different characteristics of an influencer may appeal to various content types and contexts. For example, a study conducted by Shin and Han (2019) found that physical attractiveness and familiarity with beauty influencers had no statistically significant effect on consumers’ purchase intention. Given that CPVs influencer exhibits very limited verbal expressions, foreign users might have been more drawn to exterior beauty and felt close to these influencers. Meanwhile, only trustworthiness of CPVs influencer was positively related to intention of word-of-mouth. This indicated that viewers spread words about CPVs only when they could trust the source. If CPVs influencer aims to increase the number of views or subscribers, it is essential to earn viewers’ trust. In other words, if the primary objective of CPVs influencer and cultural authorities is to promote the Chinese culture or to create a favorable image of the Chinese culture, they should develop strategies to enhance trustworthiness as a source.

Regarding CPVs content attributes, the informativeness of CPVs content was the most influential characteristic affecting travel intention. This result is consistent with previous studies in that “information pursuit” is a significant predictor of viewers’ behavioral intentions (DeMarree et al., 2017). When CPVs are perceived to have informational value to foreign viewers, these pastoral videos can be an effective promoting tool for Chinese tourism and culture. This suggests that CPVs have soft power potentials to draw interests in various aspects of the Chinese culture and to foster desires to visit.

When analyzing variables related to PSI dimensions, physical attractiveness and familiarity of CPVs influencer and technicality of content showed positive associations with BPSI. This indicated that if content providers aim to increase the number of views and interactions, such as likes and comments, they should be more attentive to offering technically savvy content with influencers whose appearances are attractive and whose vibes are warm. In term of CPSI, physical attractiveness, familiarity of influencers as well as informativeness, technicality, entertainment of CPVs content were positively related to CPSI. Once again, attractiveness and familiarity turned up as essential attributes for parasocial interactions akin to friendships, which may lead to a fandom with the influencer. However, it should be noted that this kind of result may be applicable to influencers dealing with somewhat unfamiliar, foreign cultural content. For viewers to feel these influencers as part of the same group or peers, the content should present a novel video with useful information and superior editing. Since a vast amount of new content is available to viewers on social media, the need for technically superior content seems on the rise.

CPSI which involves perceptions of camaraderie with the influencer, and BPSI which includes behaviors of communicating with the influencer were found to have positive effects on viewers’ intention to visit China and intention of WoM about CPVs. Compared to other types of content, CPVs usually do not contain commercial content and present rural livestyles including traditional cooking and handcrafting. As viewers feel inclination to become close with these influencers as friends and to interact with them, viewers are likely to visit Chine in the future and to spread words about these Chinese pastoral contents. In term of mediating effect of PSI, both CPSI and BPSI they have played a significant mediating role in the relationship between CPVs related variables and viewers’ behavioral intentions. Specifically, the relationship between attributes of CPVs content, intention to visit China, and intention of WoM about CPVs were fully mediated by CPSI. The relationships between characteristics of CPVs influencer, intention to visit China and intention of WoM about CPVs were partially mediated by CPSI. This result proved again the significance of para-social interaction in affecting viewers’ behavioral intentions. Therefore, producers or relevant parties of CPVs should consider a natural affinity with viewers and plans for generating more opportunities for viewer engagement. For instance, influencers could host onsite events, such as selecting top 10 comments or offering quiz events about the videos, which in turn, could lead viewers to expressing their thoughts and feelings in a more engaging manner.

This study discovered that CPVs, as a form of cultural export, could influence non-Chinese viewers’ intention to visit China and spread WoM. In addition, the study identified significant attributes of content and the influencer that could directly affect viewers’ behavioral intentions. Specifically, the results can provide practical recommendations regarding important characteristics of an influencer. For instance, a sense of familiarity or warmth should be emphasized when selecting an influencer for CPVs to enhance intention of visit. Informativeness of CPVs content should be the primary condition to promote the channel or the influencer. The results also shed additional light on the mediating role of parasocial interaction. While previous studies on social media influencers focused primarily on their roles with brand-related and purchase variables, this study expanded to examine the potential of cultural content such as CPVs as people increasingly consume content across cultural borders. It is conceivable that CPVs can become an effective yet unofficial channel for promoting the Chinese culture and that CPVs have the potentials to construct a bridge of intercultural communication between China and other cultures. These contents could help non-Chinese community, for example, western viewers, to gain a sense of familiarity with a traditional and rural culture of China and to foster more significant non-governmental cultural exchanges.

Limitations and Future Research

This current study is not without its limitations. First, the sample consisted solely of Americans. It is possible that American participants may exhibit a greater interest in rural Chinese scenery than individuals from other cultural backgrounds. It would be productive to test whether the results hold with individuals from different countries. Future study could investigate how cultural differences impact the utilization and outcomes of cultural contentes such as CPVs.

Second, while this study identified key factors related to CPVs influencer and content associated with intentions of visiting China and spreading word of CPVs, it also recognized that other relevant factors could affect the process but were not included in our research. Future study could investigate other factors pertaining to receivers such as users’ motivation for engaging with CPVs contents, levels of cultural acceptance and perception of CPVs influencer as an opinion leader in relation to similar cultural/behavioral intentions.

Third, although this study controlled for attitudes toward the Chinese culture and demographic factors, other relevant factors could influence the evaluation of CPVs. For instance, Netflix users who had previously watched foreign content on other platforms were likely to show an increased interest in and viewing of foreign content (Limov, 2020). Therefore, future research should deal with factors related to social media consumption of Chinese culture-related content. Measures of the average daily viewing frequency and binge-watching frequency are of interest. Additionally, future study could also control factors related to preexisting affinities for CPVs content, such as years of lived in China and frequency of travel to China, to ensure more accurate results (Limov, 2020). Finally, this study selected two CPVs contents from only female influencers. According to social identity theory (Tausch et al., 2010), individuals may feel a stronger connection with influencer of the same gender. Therefore, future research could employ other methods, such as experimental designs, to explore causal relationships among specific variables in CPVs content of different genders (e.g., male, female). Depsite these limitations, this study sheds light on the effects of the Chinse pastoral videos on international viewers from the perspective of cultural export and emphasized their significant role of the Chinese pastoral videos in promoting the Chinese culture.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authos.

References

-

Alba, J. W., & Hutchinson, J. W. (1987). Dimensions of consumer expertise. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(4), 411–454.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/209080]

-

Aleti, T., Pallant, J. I., Tuan, A., & Van Laer, T. (2019). Tweeting with the stars: Automated text analysis of the effect of celebrity social media communications on consumer word of mouth. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 48(1), 17–32.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2019.03.003]

- Amelina, D., & Zhu, Y. Q. (2016). Investigating effectiveness of source credibility elements on social commerce endorsement: The case of Instagram in Indonesia. PACIS 2016: Proceedings of the 20th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (232). AIS eLibrary.

- Arviansyah, Dhaneswara, A. P., Hidayanto, A. N., & Zhu, Y. Q. (2018). Vlogging: Trigger to impulse buying behaviors. PACIS 2018: Proceedings of the 22nd Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (249). AIS eLibrary.

-

Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. (1974). Physical attractiveness. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 7, 157–215.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60037-4]

- Byun, H. (2018). Analyzes the characteristics in the contents production and usage environment of YouTube and its popular channels; and examination of its implications. A Treatise on the Plastic Media, 21(4), 227–239.

-

Cappella, J. N., & Li, Y. (2023). Principles of effective message design: A review and model of content and format features. Asian Communication Research, 20(3), 147–174.

[https://doi.org/10.20879/acr.2023.20.023]

-

Chekima, B., Chekima, F. Z., & Adis, A. A. A. (2020). Social media influencer in advertising: The role of attractiveness, expertise and trustworthiness. Journal of Economics and Business, 3(4), 1507–1515.

[https://doi.org/10.31014/aior.1992.03.04.298]

-

Choi, G. Y., & Behm-Morawitz, E. (2017). Giving a new makeover to STEAM: Establishing YouTube beauty gurus as digital literacy educators through messages and effects on viewers. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 80–91.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.034]

-

Choi, H. J., & Jung, Y. J. (2018). The effect of beauty UCC information characteristics on information satisfaction and Information Acceptance. Journal of the Korea Entertainment Industry Association, 12(6), 75–85.

[https://doi.org/10.21184/jkeia.2018.8.12.6.75]

- Cunningham, N., & Bright, L. F. (2012). The tweet is in your court: Measuring attitude towards athlete endorsements in social media. International Journal of Integrated Marketing Communications, 4(2), 73–87.

-

Dehghani, M., Niaki, M. K., Ramezani, I., & Sali, R. (2016). Evaluating the influence of YouTube advertising for attraction of young customers. Computers in Human Behavior, 59, 165–172.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.01.037]

-

DeMarree, K. G., Clark, C. J., Wheeler, S. C., Briñol, P., & Petty, R. E. (2017). On the pursuit of desired attitudes: Wanting a different attitude affects information processing and behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70, 129–142.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.01.003]

-

Dibble, J. L., Hartmann, T., & Rosaen, S. F. (2016). Parasocial interaction and parasocial relationship: Conceptual clarification and a critical assessment of measures. Human Communication Research, 42(1), 21–44.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12063]

-

Fei, C., & Lee, J. S. (2021). The impact of the educational influencer characteristics of the short video app Tik Tok on the intention to purchase online knowledge content. A Journal of Brand Design Association of Korea, 19(2), 77–94.

[https://doi.org/10.18852/bdak.2021.19.2.77]

-

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313]

-

Freberg, K., Graham, K., McGaughey, K., & Freberg, L. A. (2011). Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relations Review, 37(1), 90–92.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.11.001]

-

Godey, B., Manthiou, A., Pederzoli, D., Rokka, J., Aiello, G., Donvito, R., & Singh, R. (2016). Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 69(12), 5833–5841.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.181]

-

Guo, C., & Abidin, C. (2021). Liziqi and Chinese rural YouTube videos: Scoping a genre. AoIR 2021: Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Conference of the Association of Internet Researchers.

[https://doi.org/10.5210/spir.v2021i0.12178]

-

Hartmann, T. (2008). Parasocial interactions and paracommunication with new media characters. In E. A. Konijn, S. Utz, M. Tanis, & S. Barnes (Eds.), Mediated interpersonal communication (pp. 177–199). Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203926864-18]

-

Hartmann, T., Schramm, H., & Klimmt, C. (2004). Personenorientierte medienrezeption: Ein Zwei-Ebenen-Modell parasozialer Interaktionen. Publizistik, 49(1), 25–47.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11616-004-0003-6]

-

Horton, D., & Wohl, R . R . (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry, 19(3), 215–229.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049]

-

Hovland, C. I., & Weiss, W. (1951). The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opinion Quarterly, 15(4), 635–650.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/266350]

- Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H. (1953). Communication and persuasion. Yale University Press.

-

Hughes, C., Swaminathan, V., & Brooks, G. (2019). Driving brand engagement through online social influencers: An empirical investigation of sponsored blogging campaigns. Journal of Marketing, 83(5), 78–96.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242919854374]

-

Hwang, K., & Zhang, Q. (2018). Influence of parasocial relationship between digital celebrities and their followers on followers’ purchase and electronic word-of-mouth intentions, and persuasion knowledge. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 155–173.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.029]

-

Jin, S. V., Ryu, E., & Muqaddam, A. (2018). Dieting 2.0!: Moderating ef fects of Instagrammers’ body image and Instafame on other Instagrammers’ dieting intention. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 224–237.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.06.001]

-

Kanaveedu, A., & Kalapurackal, J. J. (2022). Influencer marketing and consumer behaviour: A systematic literature review. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective. Advance online publication.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/09722629221114607]

-

Kelman, H. C. (1958). Compliance, identification, and internalization three processes of attitude change. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2(1), 51–60.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/002200275800200106]

- Kendall, P. (2019). The sounds of social space: Branding, built environment, and leisure in urban China. University of Hawaii Press.

- Kim, C., Jin, M. H., Kim, J., & Shin, N. (2012). User perception of the quality, value, and utility of user-generated content. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 13(4), 305–319.

-

Kim, E. H., Yoo, D., & Doh, S. J. (2021). Self-construal on brand fan pages: The mediating effect of para-social interaction and consumer engagement on brand loyalty. Journal of Brand Management, 28(3), 254–271.

[https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-020-00211-9]

-

Kim, H. (2022). Keeping up with influencers: Exploring the impact of social presence and parasocial interactions on Instagram. International Journal of Advertising, 41(3), 414–434.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2021.1886477]

-

Kitirattarkarn, G. P., Araujo, T., & Neijens, P. (2019). Challenging traditional culture? How personal and national collectivism-individualism moderates the effects of content characteristics and social relationships on consumer engagement with brand-related user-generated content. Journal of Advertising, 48(2), 197–214.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1590884]

- Klimmt, C., Hartmann, T., & Schramm, H. (2013). Parasocial interactions and relationships. In Psychology of entertainment (pp. 291–313). Routledge.

-

Knoll, J., & Proksch, R. (2017). Why we watch others’ responses to online advertising - Investigating users’ motivations for viewing user-generated content in the context of online advertising. Journal of Marketing Communications, 23(4), 400–412.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2015.1051092]

-

Lee, J. E., & Watkins, B. (2016). YouTube vloggers’ influence on consumer luxury brand perceptions and intentions. Journal of Business Research, 69(12), 5753–5760.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.171]

-

Lee, J. H., & Hwang, G. Y. (2018). An influence of service quality of SNS on users satisfaction and word of mouth intention. The e-Business Studies, 19(1), 123–134.

[https://doi.org/10.20462/TeBS.2018.2.19.1.123]

-

Lee, M. T., Yi, J., & Shim, S. (2020). An exploratory study on the effect of YouTube beauty influencer attributes on contents attitude, product attitude, word of mouth intention, and purchase intention. The Korean Journal of Advertising, 31(5), 117–142.

[https://doi.org/10.14377/KJA.2020.7.15.117]

-

Lee, Y., & Koo, J. (2015). Athlete endorsement, attitudes, and purchase intention: The interaction effect between athlete endorser-product congruence and endorser credibility. Journal of Sport Management, 29(5), 523–538.

[https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2014-0195]

-

Li, J., & Adnan, H. M. (2023a). Exploring the role of productive audiences in promoting intercultural understanding: A study of Chinese YouTube influencer Liziqi’s channel. Studies in Media and Communication, 11(4), 173–184.

[https://doi.org/10.11114/smc.v11i4.6021]

- Li, J. , & Adnan, H. M. (2023b). Social media influencers’ visual framing of Chinese culture on YouTube. Multicultural Education, 9(3), 31–40.

-

Li, J., Adnan, H. M., & Gong, J. (2023). Exploring cultural meaning construction in social media: An analysis of Liziqi’s YouTube channel. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 23(4), 1–12.

[https://doi.org/10.36923/jicc.v23i4.237]

- Li, X. (2019). Kuawenhua shijiao xia Li Ziqi duan shipin yanjiu: Yi YouTube wei Beijing [A cross-cultural perspective on Li Ziqi’s short videos: A study with YouTube as the background]. Xinwen Chuanbo, 22, 39–40+45.

-

Liang, L. (2022). Consuming the pastoral desire: Li Ziqi, food vlogging and the structure of feeling in the era of microcelebrity. Global Storytelling: Journal of Digital and Moving Images, 1(2), 7–39.

[https://doi.org/10.3998/gs.1020]

- Liang, Z. J. (2023). Tan tan Zhonghua wenhua de zou chu qu zhanlue: Yi Li Ziqi shipin wei li [Discussing the strategy of promoting Chinese culture abroad: A case study of Li Ziqi’s videos]. Xinwen Chuanbo, 1, 25–27.

- Limov, B. (2020). Click it, binge it, get hooked: Netflix and the growing U.S. audience for foreign content. International Journal of Communication, 14, 6304–6323.

- Lin, C. A., Crowe, J., Pierre, L., & Lee, Y. (2021). Effects of parasocial interaction with an Instafamous influencer on brand attitudes and purchase intentions. The Journal of Social Media in Society, 10(1), 55–78.

-

Liu, X., Park, J. Y., & Lee, H. E. (2020). The effect of Wang-Hong characteristics on impulse buying during live sale: Based on women’s clothing sales in China. Journal of the Korea Content Association, 20(4), 212–229.

[https://doi.org/10.5392/JKCA.2020.20.04.212]

-

Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501]

-

Luo, X. L., Zhu, J. Y., Gleisner, R., & Zhan, H. Y. (2011). Effects of wet-pressing-induced fiber hornification on enzymatic saccharification of lignocelluloses. Cellulose, 18(4), 1055–1062.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-011-9541-z]

-

Manchanda, P., Arora, N., & Sethi, V. (2022). Impact of beauty vlogger’s credibility and popularity on eWOM sharing intention: The mediating role of parasocial interaction. Journal of Promotion Management, 28(3), 379–412.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2021.1989542]

-

Martensen, A., Brockenhuus-Schack, S., & Zahid, A. L. (2018). How citizen influencers persuade their followers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 22(3), 335–353.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/jfmm-09-2017-0095]

-

McGuire, W. J. (2001). Input and output variables currently promising for constructing persuasive communications. In R. E. Rice & C. K. Atkin (Eds.), Public communication campaigns (3rd ed., pp. 22–48). SAGE Publications.

[https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452233260.n2]

-

Mikalef, P., Giannakos, M., & Pateli, A. (2013). Shopping and word-of-mouth intentions on social media. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 8(1), 17–34.

[https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-18762013000100003]

-

Moon, M. (2023). Media coverage of K-pop by BBC and CNN: A corpus-assisted discourse analysis. Asian Communication Research, 20(3), 234–249.

[https://doi.org/10.20879/acr.2023.20.022]

-

Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., & Deshpande, R. (1992). Relationships between providers and users of market research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3), 314–328.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/3172742]

-

Munnukka, J., Uusitalo, O., & Toivonen, H. (2016). Credibility of a peer endorser and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 33(3), 182–192.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/jcm-11-2014-1221]

- Nandagiri, V., & Philip, L. (2018). Impact of influencers from Instagram and YouTube on their followers. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Modern Education, 4(1), 61–65.

-

Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising, 19(3), 39–52.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673191]

-

Park, J., & Lee, Y. (2021). Luxury haul video creators’ nonverbal communication and viewer intention to subscribe on YouTube. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 49(6), 1–15.

[https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.10119]

- Rasmussen, L. (2018). Parasocial interaction in the digital age: An examination of relationship building and the effectiveness of YouTube celebrities. The Journal of Social Media in Society, 7(1), 280–294.

-

Rubin, A. M., & Step, M. M. (2000). Impact of motivation, attraction, and parasocial interaction on talk radio listening. Journal of Broadcasting & Electric Media, 44(4), 635–654.

[https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4404_7]

-

Schramm, H., & Hartmann, T. (2008). The PSI-process scales. A new measure to assess the intensity and breadth of parasocial processes. Communications, 33(4), 385–401.

[https://doi.org/10.1515/COMM.2008.025]

-

Schramm, H., & Wirth, W. (2010). Testing a universal tool for measuring parasocial interactions across different situations and media. Journal of Media Psychology, 22(1), 26–36.

[https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000004]

-

Shin, K. A., & Han, M. (2019). Exploratory survey on factors involved in endorsement potentials of YouTube influencers: Characteristics of influencers, characteristics of video contents, and para-social interactions. Journal of Public Relations, 23(5), 35–71.

[https://doi.org/10.15814/jpr.2019.23.5.35]

-

Silk, M., Correia, R., Veríssimo, D., Verma, A., & Crowley, S. L. (2021). The implications of digital visual media for human-nature relationships. People and Nature, 3(6), 1130–1137.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10284]

-

Sokolova, K., & Perez, C. (2021). You follow fitness influencers on YouTube. But do you actually exercise? How parasocial relationships, and watching fitness influencers, relate to intentions to exercise. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102276.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102276]

- Stoeckl, R., Rohrmeier, P., & Hess, T. (2007). Motivations to produce user generated content: Differences between webloggers and videobloggers. Bled 2007: Proceedings of the 20th Bled eConference (pp. 398–413). AIS eLibrary.

- Supriyanto, A., Jayanti, T., Hikmawan, M. A., Zulfa, F. N., & Fanzelina, A. S. (2023). The influence of perceived credibility, trustworthiness, perceived expertise, likeability, similarity, familiarity, and attractiveness on purchase intention: A study on halal bakery products in Kudus regency. NIZAM: International Journal of Islamic Studies, 1(1), 29–45.

- Tausch, N., Schmid, K., & Hewstone, M. (2010). The social psychology of intergroup relations. In G. Salomon & E. Cairns (Eds.), Handbook on peace education (pp. 75–86). Taylor and Francis.

-

Torres, P., Augusto, M., & Matos, M. (2019). Antecedents and outcomes of digital influencer endorsement: An exploratory study. Psychology & Marketing, 36(12), 1267–1276.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21274]

-

Valentini, C., Romenti, S., Murtarelli, G., & Pizzetti, M. (2018). Digital visual engagement: Influencing purchase intentions on Instagram. Journal of Communication Management, 22(4), 362–381.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-01-2018-0005]

-

Verhagen, T., & van Dolen, W. (2011). The influence of online store beliefs on consumer online impulse buying: A model and empirical application. Information & Management, 48(8), 320–327.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2011.08.001]

- Virno, P. (2004 ). A grammar of the multitude. Semiotext.

-

Wang, X. (2022). Kuawenhua chuanbo shiye xia Zhongguo xiangcun shenghuo lei shipin de fuhaoxue fenxi: Yi Li Ziqi YouTube shipin wei li [Semiotic analysis of Chinese rural life videos from the perspective of cross-cultural communication: Taking Li Ziqi’s YouTube videos as an example]. Audiovisual, 11, 20–22.

[https://doi.org/10.19395/j.cnki.1674-246x.2022.11.009]

-

Wei, D., Wang, Y., Liu, M., & Lu, Y. (2024). User-generated content may increase urban park use: Evidence from multisource social media data. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 51(4), 971–986.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/23998083231210412]

-

Wiedmann, K. P., & von Mettenheim, W. (2021). Attractiveness, trustworthiness and expertise - Social influencers’ winning formula? Journal of Product & Brand Management, 30(5), 707–725.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2019-2442]

- Yu, J., & Zhang, Y. R. (2021). Zhongguo Wanghong zai YouTube Zhong de duanshipin kuawenhua chuanbo fenxi - Jiyu shige Zhongguo Wanghong de duanshipin neirong fenxi [Cross-cultural analysis of Chinese weblebrities’ short videos in YouTube - Based on the short video content analysis of ten Chinese weblebrities]. Southeast Communication, 5, 77–80.

- Zhang, X. X. (2022). Li Ziqi duan shipin zuopin chenggong zhi dao [The key to the success of Li Ziqi’s short video works]. Xibu Guangbo Dianshi, 20, 87–89.

-

Zhang, X., Wang, L., Pang, Q., & Bae, K. H. (2021). The influence of China’s network video features on consumer subscription satisfaction and continuous subscription intentions. Journal of the Korea Content Association, 21(12), 423–435.

[https://doi.org/10.5392/JKCA.2021.21.12.423]

-

Zhang, Y., Li, J., Liu, C. H., Shen, Y., & Li, G. (2021). The effect of novelty on travel intention: The mediating effect of brand equity and travel motivation. Management Decision, 59(6), 1271–1290.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/md-09-2018-1055]