An Informal Narrative Provider: An Overview of “Homma” Culture in the Context of K-Pop Idol Culture

Copyright ⓒ 2024 by the Korean Society for Journalism and Communication Studies

Abstract

Homma, a distinct group of fans within the K-pop culture, devotes itself to capturing and sharing images of beloved celebrities through high-quality photography and skilled retouching. Although often labeled as fan paparazzi or stalker fans, K-pop fan communities generally regard Homma with respect, recognizing them as vital contributors to celebrity photography consumption. Despite its cultural significance, Homma remains understudied by K-pop scholars. This research explores the dynamic relationships between Homma and the K-pop industry and the fan community within the domestic K-pop landscape. Drawing on the literature on celebrity studies and celebrity narratives, I argue Homma format, as an informal narrative provider contextualized in the celebrity-narrative centered K-pop idol industry, not only serves as an essential source of the collective narrative in the fan community but also takes the promotional roles selling their beloved celebrities to the other audience. This study will primarily be based on my empirical studies in South Korea (from 2016–2019) and online participatory observation in the K-pop fan communities (from 2016 till now), as well as a semi-constructed interview with a current active Homma in Seoul, South Korea.

Keywords:

K-pop idol culture, Homma, K-pop industry, fan studies, celebrity studies, celebrity photographs“Homma”(Homepage Master, 홈마) refers to a particular type of fan who takes pictures or videos of a celebrity and shares them on the social media accounts. Homma can often be seen in various K-pop scenes, including but not limited to airports, concerts, public events, fan sign events, and going-to-work scenarios. Although South Korean news and the public often label them as paparazzi (Oh, 2019) or Sasaeng fans (사생, stalker fans) (Lee, 2019) because of how they always follow and shoot the idol on different occasions, in K-pop fandom, Homma is highly differentiated from the Sasaeng fans and usually treated with respect. Popular Homma of top K-pop idols like BTS on X (previously Twitter) can attract more than 2 million followers from all over the world (e.g., @_nuna_v), with all the comments showing appreciation to the Homma. Despite most being amateur photographers, Hommas are essential contributors to the K-pop fan culture in the East Asian region. They serve as important channels for promoting their idols. A renowned example would be the case of Hani, a former member of the K-pop girl group EXID. Hani's company employed various strategies to promote the group, but her breakthrough occurred when a video taken by one of her Hommas went viral on YouTube. Even though Homma culture plays a significant role in K-pop culture, limited research has investigated this fan culture in South Korea. This study focuses on the Homma format in South Korea to discuss its significance in the K-pop cultural landscape.

Previous studies on Homma culture situate its development within the technological advancement in South Korea (Kim, 2018) and explore the secondary activities of Homma culture, such as merchandise selling (Kim, 2018; Lee & Ji, 2015), as well as its role in the K-pop culture (Fa, 2019; Han et al., 2018). This research correlates Homma culture to narrative production in K-pop idol culture, viewing it as a crucial provider of celebrity narratives. The research addresses the following questions: What is the Homma format, and how does it differ from other celebrity photography/video genres? What characteristics of the K-pop industry and fan culture have given rise to the unique Homma culture? What value does Homma contribute to the K-pop industry and the K-pop fan community? Based on Neal Gabler’s (2001) definition of celebrity as a type of narrative and existing scholarship on celebrity narratives, this research defines Hommas as informal narrative providers who direct an affectionate “fan lens” that narrows the distance between fans and idols creating a sense of comfortable intimacy. I argued that as informal text producers and promoters of their K-pop idols, Hommas provide distinct perspectives that differ from the formal/official and photojournalistic narratives, filling the gaps that other channels fail to address. Driven by the fan perspective, the Homma format navigates between private and public spaces situated within the narrative-centered K-pop idol industry. Homma culture serves not only as an essential source of collective narratives in the fan community but also as promoters who market their beloved celebrities to a broader audience.

This research is based on three years of empirical observations in Seoul, South Korea, from September 2016 to August 2019, as well as online participatory observations of K-pop fan communities, supplemented by a semi-structured interview conducted in November 2023 with an active Homma (referred as Homma J) to ensure the continued relevance of my findings. While regularly consuming Homma productions, I closely observed several fellow fans participating in Homma activities, focusing on their transition from ordinary fans to Hommas. During my fieldwork, I conducted offline observations of fan photography activities in public spaces, including gatherings outside broadcast companies for celebrity photo shoots, recording events, fan signings, and fan-organized activities. I also engaged in ongoing conversations with Hommas before, during, and after these events. I initially met these Hommas in offline events of two different fandoms, and we maintained contact even after they transitioned to other fan communities, where they continued their Homma activities in both popular K-pop idol fandoms and smaller fan communities. Each observed Homma was informed about my research, and I obtained their consent to include their experiences in this study. To ensure anonymity, these individuals are referred to as Homma Y, Homma C, and Homma J in my analysis. Additionally, this study incorporates posts from other Hommas on social media, online discussions about Homma culture, and other relevant materials.

An Overview of Homma Literature

A Homma is commonly defined as a fan who actively posts photos and videos of beloved stars on online “homepages” (Han et al., 2018; Kim, 2018). Their photographs are not atrocious amateur works but could often be comparable to those of professional journalists or are of higher quality and output. (Fa, 2019; Han et al., 2018; Kim, 2018). Thus, the development of Homma is closely related to the rapid development of digital technology and increasing accessibility and affordability of digital equipment to the general public, especially the digital camera and software technologies developed in Korea (Kim, 2018). Moreover, with leading Internet speeds and “connectivity” in the late 1990s, increasing numbers of K-pop-related videos and information could be shared and spread on South Korean online spaces (Hong, 2017, p. 71). Before the development of social media, some of the fans uploaded and shared their favorite stars' information and images on their web pages, often called “homes.” Consequently, these fans were often called “Homepage Master” (short for Homma) (Kim, 2018).

In addition to the historical development, previous scholars have also paid attention to the motivation and the role of Hommas in the K-pop world. Although some Hommas decide to shoot their idols because of aiming for intimacy with their idols and the reputation within the fan community (Fa, 2019), many others, as “nurturers”, try to produce more satisfying content than those produced by official channels or photojournalists for fan consumption (Kim, 2018), or help to promote their idols (Fa, 2019). Hommas’ production often wins more favor from fans than the official ones, primarily because of their affection toward idols and the competition among Hommas that leads to the production of high-quality (Kim, 2018; Lee & Ji, 2015). Recognizing the value of Homma in fan communities, K-pop entertainment companies and idols also directly or indirectly cooperate with Hommas: K-pop companies sometimes stay in contact with Hommas and reveal idols’ schedules (Kim, 2018) while K-pop idols purposefully respond to Hommas by looking at their cameras (Fa, 2019).

Scholars generally believe that Hommas are motivated not by profit but by a desire to serve their fan community better. According to studies by Han et al. (2018) and Kim (2018), Hommas typically reinvest the earnings from their merchandise into covering shooting costs or participating in “Jogong,” a gift-giving activity popular among K-pop fan communities where fans collectively raise funds to buy presents for their beloved idols. As a result, many fans do not view Hommas as high-status prosumers within the fan community but rather as individuals who sacrifice their time and money for the benefit of the fan community or idols (Lee & Ji, 2015). By dedicating their effort and financial resources, Hommas produce high-quality photos and fanmade products, engaging in a service-oriented form of unpaid labor (Fa, 2019). However, this does not imply that all Hommas exclusively perform free labor; many active Hommas in large K-pop fan communities with numerous followers also earn significant profits by selling their fanmade products. For many Hommas, selecting a fan circle with potential economic benefits is seen as a long-term investment in the K-pop fandom (Kim, 2018).

Previous studies have delved into how Homma culture was closely related to digital technology and internet development in South Korea. The continued development of Homma culture also aligns with the Korean Wave 2.0, characterized by increased involvement with digital media and converging communication (Harris, 2022), along with the globalization of the Korean pop music industry. This research focuses on how the Homma phenomenon has emerged in the K-pop idol industry from the cultural perspective, particularly in the uniqueness of the K-pop culture industry, which is centered on creating narratives of the entertainers. The subsequent section focuses on the literature concerning common celebrity narratives, including those created by photojournalists, official sources, and fans, to distinguish these from the celebrity narratives produced by Hommas.

Celebrity and Celebrity Narratives

Boorstin (1992) defined a celebrity as a “person who is known for his well-knownness,” a “pseudoevent” with no substantial greatness as a “hero” but merely a reflection of supporters’ sense of emptiness. He argues that it seems unreasonable that entertainers who do not contribute significantly to society achieve more attention and worship than other deserving greats (Boorstin, 1992). Instead of getting caught up in endless debates about the social value of celebrity, viewing the celebrity as an art form seems to be a more appropriate premise for a discussion related to how an audience perceives and understands a celebrity (Gabler, 2001). Gabler thus framed celebrity as a type of narrative like other art forms in that their ongoing life chapters drive the vehicle for storytelling and can entertain the audience. Their lives inherently provide entertainment, and the segments of their existence resemble plotlines in a film, continually holding the potential for exploration (Gabler, 2001). The most appealing aspect of celebrity as an artistic narrative, especially for artists who are still active in various media, is that the celebrity narrative is a story without a last chapter. There is a continual anticipation of the future that creates suspense for the viewers (Tataru, 2012). Each time when celebrities are featured in the media and presented in different roles in conventional media forms, they unlock new characterization possibilities, like the protagonist in a movie entering a new storyline (Gabler, 2001). Additionally, the readers and celebrities coexist within the same worldview (the real world), fostering intimacy and a feeling of authenticity rooted in shared experiences and similar sentiments hardly replaceable by alternative media forms.

While everyone’s life can be a narrative, one of the key requirements for stardom is that the narrative must be well-known. Thus, Gabler (2001) recognizes Boorstin’s account that “well-knownness” is at the heart of stardom and that the two main elements that build a star’s popularity are “foundation narrative” and publicity. The “foundation narrative” is how celebrities become known to the public in the first place, whereas publicity aims to present the appealing sides of the celebrities to attract more attention from the public (Gabler, 2001). In addition to celebrity-related interviews, variety shows, and press releases, the most common form of publicity is celebrity photographs. Existing studies of celebrity photographs for publicity mainly focus on officially released photography, journalistic photography (news), and celebrity auto-photographs. Most of these categories fall somewhere between “editorial” and “promotional” photography (Squiers, 1999). Howells (2011) connected celebrity photographs to ancient heroic relics and underscored the significance of the idea of “presence” in celebrity photography. The celebrities’ appearances inherently create value to be captured. These officially controlled photographs are not only able to cater to the future career trajectory of celebrities but also to create a positive image and boost popularity among the public.

Greatly different from official agencies, entertainment news (excluding those who collaborate with celebrities) and paparazzi focus on uncovering mundane everyday looks and controversial daily events out of the “extraordinary” (Mortensen & Jerslev, 2014). For example, the early celebrity photographs in tabloids aimed to capture the candid image of celebrities and satisfy the voyeuristic desire of their readers, transforming how the public had perceived the distanced public figures (Linkof, 2020). Paparazzi only capture photographs of celebrities who are considered valuable targets. Specifically, paparazzi prefer provocative plots that clash with the upbeat “extraordinary” to attract attention from the public and to create buzz, thus often taking or framing the story “unethically” in compromised situations for the stars (Mortensen & Jerslev, 2014). This explains why paparazzi put considerable effort into stalking celebrities, often disregarding ethical standards in the process (Howe, 2005). However, with the increasing exposure of celebrities in various media, paparazzi also collaborate with some celebrities, shooting the “ordinary” sides to help shape their desired images (Ramamurthy, 2021).

Currently, limited research focuses on fan involvement as photographers in celebrity photography other than the Homma literature. Nevertheless, studies focusing on fans’ perception of celebrity narratives and the buildings of those narratives still hold significant importance in understanding the fan photographers' motivation behind them and the value of their photography. Fans engage in constructing their narratives for various reasons. On the one hand, they express dissatisfaction with “publicity” institutions that conceal or distort celebrities’ private life events crucial to understanding the development of their life story, seeking to uncover the genuine aspects of a celebrity’s identity (Thomas, 2014). On the other hand, as previously mentioned, official sources and news tend to adopt an editorial or “promotional” perspective on celebrities’ characterization (Squiers, 1999). These sources selectively present the personality of a celebrity based on their viewpoints and needs, subject to editing and reframing. As a result, it becomes challenging for the audience to form a comprehensive and multidimensional narrative, requiring them to imagine and supplement existing information to create a more complete storyline (Horton & Wohl, 1956). This narrative building inevitably diverges from the authentic textual representation of the celebrity. Still, it holds particular significance in appreciating the narratives when the audience tries to understand and interpret a celebrity’s persona and life story. In a study exploring offline celebrity fan encounters, fans who have interacted with celebrities in person compile their observations into episodes, constructing new narratives shared by the fan community. These fan-generated narratives draw on segments from official publicity narratives, mutually relying on and being reconstructed into a “real” characterization of the celebrity, thus further disseminated on the internet beyond the fan circles (Harris, 2022). Consequently, as fans consume the stories of celebrities, they are also constructing their collective narratives and interpreting the celebrity narratives. By establishing emotional connections through stories and the portrayal of a celebrity's character, fans immerse themselves in the emotional twists and turns, leading to a profound sense of pleasure (Batty, 2014).

Contextualizing Homma in K-Pop Idol Culture

K-pop idols are characterized by narratives collectively contributed to by the idols themselves, the K-pop industry, and the general public (López Del Valle, 2021). Similar to how scholars view idols in Western talent shows, the main attraction of a “K-pop idol” lies in the opportunity for fans to follow the narrative of their beloved idols’ growth, from newcomers in the music industry to superstars recognized and praised by the public (Fairchild, 2007). K-pop idols typically embody both collective and individual narratives. They debut as a group, with each member responsible for distinct roles within the group, and the solidarity of the group forms the core plot of their collective narrative (Kang & Kang, 2016), constituting the “foundation narratives” (Gabler, 2001). Compared to conventional musicians or singers, the appeal of K-pop idols extends beyond their ability to sing or dance on stage. It also includes the development of various other charms (Lee, 2023) in their “personal life stories.” Their appearances on diverse content such as variety shows, interviews, and other types of clips become collectible episodes that allow fans to construct and share the idols’ personas within the fan community and with the public. This phenomenon is evident in the Namu Wiki entries of K-pop idols, where fans contribute pieces of information to create comprehensive introductions of their idols.1 The curiosity and affection toward idols’ “life narratives” compel fans to collect any relevant information from any sources they can find. Since celebrities are real people, beyond the available official channels, any occasion that provides additional details or plots can attract curious fans, such as ordinary offline fans, sasaeng fans, and Hommas.

The curiosity and attraction of K-pop idol narratives not only allow the fan to be an audience along with the story but also actively encourage the fan to shape their idols’ life story or even be a part of it. Fans are not only the co-shapers but also the core characters in the narrative. Jung and Lee compared the cultivation of K-pop idols idol to a family unit, where the K-pop entertianment companies and fans raise their shared child -- the idol. During this process, the entertainment companies provide professional training and financial support, while fans contribute love and all efforts to shape the trajectory of the idol’s growth (Jung & Lee, 2009). This elucidates why K-pop data/metric fandom invests an enormous amount of free labor in nurturing idol success, as such collective interests of idols and fans are highly valued and prioritized. For example, fans often call their idols nae segi (translated as “my children”) or ae gi (translated as “babies”) and actively suggest or protest against companies to make the right track for their idols. The desire and expectation toward their idols provide fans with ample motivation to participate actively, fostering a group of prosumers willing to contribute more, dedicate themselves, and offer their talents (Lee & Ji, 2015). These prosumers, including Homma --one of the most crucial roles, invest their efforts and skills to become builders of the narrative, and by sacrificing for the fan groups, they not only become the narrative builders to enjoy the joy of getting their idol recognized by the public gradually, but their efforts are also appreciated and encouraged by their fellow fans (Kim, 2018).

Beyond the narrative component, the geographical traits and affordances of the K-pop industry also provide fertile ground for the emergence of Homma culture. The K-pop industry offers not only ample consumption and engagement spaces for fans from a distance and online but also provides affordable, regular, and high-frequency opportunities and diverse spaces for offline fans participating in a myriad of activities or television program recordings (Kang & Kang, 2016). Homma J describes a typical Friday during the “comeback” period of her idol:

It usually depends on my idol's schedule. On a busy Friday, I typically rent a better camera lens from Gangnam the night before and place my ladder at the designated shooting spot in front of KBS (Korean Broadcasting System) in Yeouido. In the morning, I arrive at Yeouido at 7 a.m. and take pictures of the idols’ “go-to-work” moment. Afterward, I join the line with other fans waiting to watch the recording of Music Bank. Sometimes, my idol comes out to interact with fans before the recording, and I take pictures during these moments. After the recording, I usually wait at the gate, and when my idol’s group gets into their car and drives out, they often roll down the window to greet fans, providing another opportunity to take pictures. In the afternoon, if my idol’s group has another recording at the DMC (Digital Media Center), I photograph them before they enter, after they finish, and sometimes during breaks in between. Later, around 4 p.m., I return to KBS to take photographs as my idol exits the live broadcast of Music Bank. Fan-sign events usually take place in the evening, lasting until about 10 p.m. During fan-sign events, I prepare gifts or accessories for photos and continuously take pictures before and after my turn. Afterward, I return the borrowed camera lens and take a taxi home.

Most of the K-pop-related cultural industries and companies in South Korea are in Seoul. Seoul is a relatively smaller city in size compared to many other metropolitan cities like Los Angeles and Beijing -- the major cities where the national entertainment industries are located. It also has a well-developed public transportation system, such as subways and buses, with most locations reachable within an hour of transit. Even if fans attempt to travel to the other side of the city for an offline fan event, they can easily enjoy the activity and get back home within a day. Additionally, television stations, entertainment companies, concert venues, and even coffee shops where fans engage in celebrating gatherings concentrate in a few popular areas, such as Yeouido Island, Hongdae, and the Digital Media Center (DMC) in Seoul. Especially DMC, where major South Korean television stations are located, is a strategically important area for South Korean cultural industrial development (Cohen, 2014), allowing fans to gather and participate or watch various idol recordings in a short time, creating opportunities for offline interactions between fans and idols and forming a distinctive offline activity community.

Furthermore, the activities of K-pop idols exhibit a high degree of regularity and often follow standardized patterns. Idol groups typically debut on major music ranking shows such as MBC Music Core, SBS Inkigayo, KBS Music Bank, and Mnet M Countdown, many of which are free for selected audiences (usually verified fans). During their albums’ promotional periods, idols perform in these shows weekly to ensure enough exposure to stage performances not only to their fans but also to the potential audience of the shows. For the offline fans and the Hommas, the recordings are valuable chances to see their idols’ live performances in person at a closer distance. Fan-sign event2 is another important occasion for offline activities. Entertainment companies launch multiple fan-sign events to stimulate album sales by using lotteries. Getting the signed album is not even the main goal for the “regular visitors” to the event. The opportunity to interact with the idols in a one-on-one manner and observe every moment of their idols in the event for over an hour to better understand their personality from the audience seats is the most precious gain from the fan-sign events. As for Homma, who needs to upload diverse and fresh photography of their idols on a regular basis, the unique landscape of K-pop offline activities ensures Homma plans their schedules in early advance and maintains a regular and high frequency of fan production for the fan community.

Homma Format: An Informal Narrative

I define the Homma format as an “informal narrative” that complements or challenges the narratives created by formal channels, such as entertainment agencies, TV networks, or entertainment journalists. Each Homma photograph or video captures an indexical moment of their favorite celebrities, encompassing their aura, personality, styles, and specific occasion and time. These “presences” of celebrities are valuable (Howells, 2011) because each frame serves to fill gaps in the celebrity narrative that is collectively constructed within the fan community or imagined by individual fans. This process leads to varied interpretations of the celebrity’s persona and life story (Gabler, 2001). In the following sections, I will elaborate on how Hommas function as informal narrative providers within K-pop culture, focusing on their distinct fan perspectives, the sites of their photography, and their positions within the K-pop fan community.

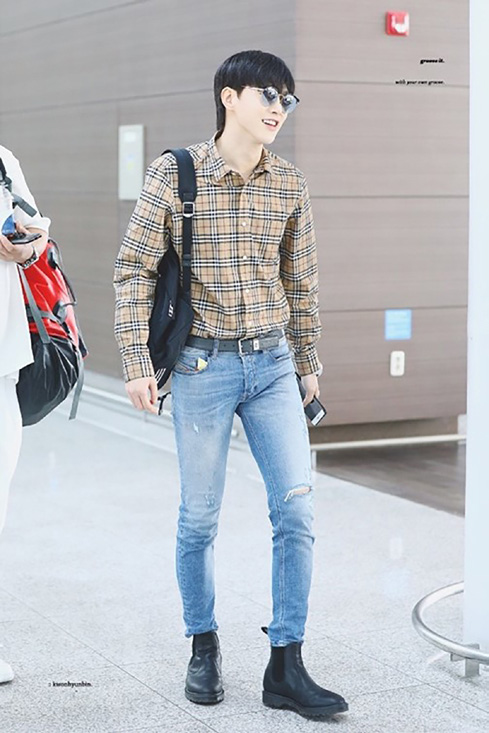

Homma format, including v ideos and photographs, is formatted in a way that is easily recognizable to the general K-pop fan community in South Korea. Unlike ordinary fan-encounter photos, the majority of active Hommas within the K-pop fan community adhere to a standardized format, making their work easily identifiable to experienced fans. Different from the homepage era, Hommas are now typically active across multiple social media platforms, including X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, YouTube, and, in some cases, Weibo. Homma account names in Korea typically do not directly indicate their affiliation with the idols but instead refer to related elements. For example, “Honeysweet” signifies the idol’s cuteness, while “Goldfish” is a nickname for the idol. Homma’s posts on social media generally include three basic elements: the date of the photograph, information about the event or recording, and hashtags, which make the content searchable for both fans and other interested viewers (Figure 1). Often, these posts contain a short description of the photo, either a brief scenario description or a simple interpretation by the Homma. For example, Figure 1 shows a Homma post on their X account (@grooveit_97) capturing the “airport look” of an idol named Kwon Hyun-bin. The text in the post is written in an affectionate tone, stating, “At that time, that beautiful baby, the baby bunny.” The hashtags serve publicity purposes, allowing anyone searching these keywords to see this attractive and charming side of the idol. Additionally, Homma includes a watermark of their logo on the picture to assert authorship (Figure 2). Timeliness and obtaining first-hand information are crucial for Hommas, especially when multiple Hommas compete for followers within a fan circle. To stay timely, many Hommas shares a “preview version” of their content without detailed editing before releasing the formal version.

Homma format is distinct from other channels of celebrity narratives primarily because it is produced from the perspective of a fan. This fan identity indicates that Hommas approach photography with a fundamentally different perspective compared to reporters or official photographers. The latter two categories generally include professional photographers, entertainment industry professionals, or journalists, whose primary motivation is their professionalism. Their shots are expected to conform to the requirements of their profession and not reflect their personal feelings about their subjects. In contrast, Hommas engage in photography as an expression of their love for their idols, with their affection serving as the primary driving force behind their work. Kim (2018) relates this “camera with affection” to “Jeong” (a feeling or emotion in Korean culture). When I asked Homma J, “Why do you think fans sometimes prefer Homma’s photos over those of photojournalists or official photographers in the same setting?” Homma J responded, “Because there is no love in their pictures.”

Homma selectively posts the most appealing photos that cater to publicity purposes and the shared narrative within the fandom. Homma’s affective creation is shaped by several aspects. First, as fans who frequently observe idols, Hommas know the most charming angles of idols from the collective fans’ perspectives. For instance, Homma Y typically selects only four pictures out of over a thousand taken at events like fan meetings and fan signs. She sometimes even seeks other fellow fans’ opinions on her photos. Since her idol is relatively short, she purposefully captures him from a lower angle. Second, experienced Hommas are familiar with which images of idols align with the collective fans' characterizations and are adept at discovering moments that satisfy fans’ imaginations of their idols. For example, the Homma @grooveit_97 further emphasizes Kwon Hyun-bin’s cute image, as established in the previous photo, by posting a preview photo with a caption saying: “Hyun-bin was asked to unfold the paper stars, so he carried the microphone under his arm TT” She added a crying “TT” emoji to express the cuteness of this moment. This photo soon virally circulated within the fan community as a charming episode in Hyun-bin’s cute persona.

Third, besides capturing charming moments and angles, the process of editing images or videos is also essential for Hommas. During the retouching process, Hommas directly shape and portray the narrative they desire, greatly influenced by their own aesthetics and perspective toward their idol. The photography reflects the unique taste of each Homma within the fan community, attracting fans with similar perspectives regarding the idols. Some Hommas prefer the “charismatic side” of an idol, so they usually choose cool-toned filters, while others prefer the idol's cute side and thus opt for warm-toned filters. In addition to retouching, many Hommas also attempt to showcase the idol's beauty with unedited photos, which have also garnered significant fan appreciation. According to a discussion thread about Homma photos on a Korean online forum, Nate Pann, many fans posted their favorite unedited Homma pictures to express their admiration for the idols’ appearance.3

Furthermore, I define Homma’s camera as a type of fan lens: When Homma’s camera lens is directed toward the idol, the gaze is from a fan’s perspective. Conversely, when the idol looks at Homma’s camera, the idol is engaging with a fan's lens (Figure 4). As previously discussed, the most crucial premise of Homma photography is that it is taken by a fan. From the fan community’s perspective, Homma is “one of us.” When an idol interacts with Homma, he is interacting with a fan, looking directly at Homma's camera. Such a camera lens often captures the idol's attitude and reaction to the fan groups. Compared to the idols’ professional demeanor in official cameras, Homma’s fan lens “guides” the fans into the scenarios, engaging them by substituting the perspective of the Homma. This creates a greater sense of intimacy and a feeling of reallife interaction, ultimately delivering significant pleasure to fans who have established emotional connections and a deeper parasocial relationship with the idols (Batty, 2014). According to my conversations with fans both online and offline, idols who can recognize their Homma’s camera and frequently respond and show “love” to it are often praised for their attentiveness and effort in acknowledging fans. As a result, these idols tend to attract more loyal fans who participate in offline events such as fan signings and other activities.

Kwon Hyunbin Shows a Finger Heart to His Homma’s CameraNote. @grooveit_97’s photography from a fan-sign event.

Most popular idols or idol groups have multiple Hommas, and each Homma, operating independently, provides the fan community with diverse angles and interpretive approaches to the narrative, influenced by their unique experiences with the idols framed in the camera. The divergent aesthetic preferences and nuanced choices made by different Hommas enable fans to piece the narrative together and attempt to recreate the circumstances surrounding the photo shoot, contributing to the understanding or reshaping of the idol’s image in the hearts of fans and the relationships between the idol and the group or other individuals. Moreover, with globalization, the demography of Hommas became more diverse with transnational cultural backgrounds. For instance, a significant portion of Hommas active in Korea are Chinese fans, which implies a potential dynamic understanding and tastes of their photography.

In addition to providing different perspectives from the formal ones, Homma tends to capture moments or occasions that are often absent from the official content, thereby filling gaps within the collective fan narratives-- what Henry Jenkins (2006) described as the “common knowledge” of the fan community. Homma photography typically locates a space between the public and private or connects the general fan audience to the privileged content, complementing narratives not addressed by official perspectives. K-pop Homma’s most common filming occasions include music shows or other locations for official schedules. The broadcasted versions of the recordings themselves are available to the public and regarded as professionally edited content. However, the gaps between the official schedules of idols in costumes or dresses are the best time for Homma to get in touch with idols and take photos.

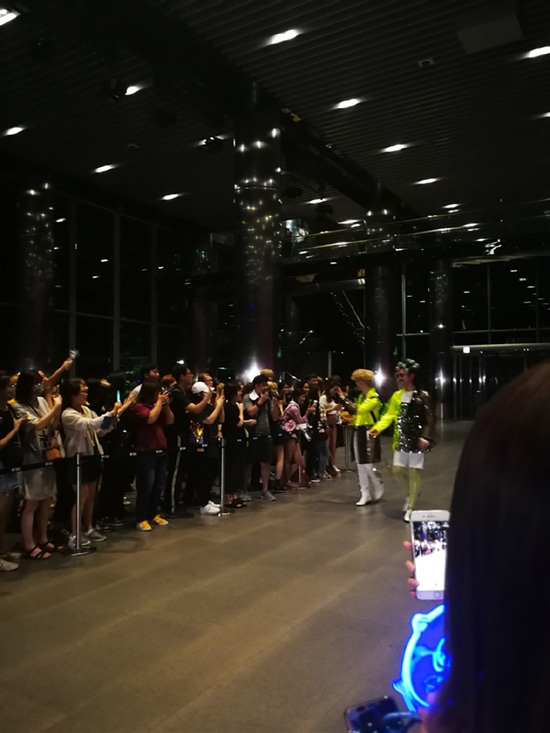

Hommas usually take photos when idols are traveling to and from work. These photographs are often called “going-to-work” looks, depicting idols’ daily routines as if they were regular office workers. The “going-to-work look” is a type of K-pop idol photograph easily recognizable to K-pop fans, primarily because most idol groups record their performances during the “comeback” period on various music shows. Hommas typically wait outside the studios and photograph their K-pop idols on their way to “work.” Among all the going-to-work venues, the most famous is the KBS Music Bank spot, where the broadcast company designates a section of the parking lot for Hommas and entertainment journalists to photograph the idols (Figure 5). By capturing idols during non-working hours in public places, Hommas can showcase a more natural and relatable side of the idols—ordinary young adults on their daily commute. For the fan community, what distinguishes a Homma from a “sasaeng” (stalker fan) is that Hommas usually obtain information about the idol’s schedules and locations through acceptable channels (e.g., official schedules and announcements from entertainment companies and production teams or by directly contacting staff, but not the idols). Hommas typically do not capture idols in their private life, adhering to the basic principle of not violating the idols' personal lives to maintain legitimacy within the fandom.

The “going-off-work” section in The Show (SBS M) inside of the SBS Building in Digital Media Center, SeoulNote. This photo captures the “going-off-work” section of a music show called The Show (SBS M). It shows idols and performers walking through the center of the building’s lobby, surrounded by Hommas and fans with cameras. (Photo taken by the author of this article, September 4th, 2018).

Another category of Homma photographic scenarios is those that require money, time, or extra effort to gain access to the interaction with idols, including concerts, offline official events, commercial performances, and fan signs. For fans unable to attend these events, Homma’s photographs serve as channels to keep track of the updated life events and continue to discover the dynamic personas of their idols, reconfiguring their imagination of the idol’s narratives. For those who have physically attended these events, Homma’s work becomes a form of storage that helps to collect the memories of their idol interactions digitally and serves for later reexamination to rediscover new facets of the idol’s characterization. Many offline K-pop fan sign sessions allow fans to bring various accessories or costumes for idols to wear (Figure 4). For Hommas, these events not only provide an opportunity to capture close-up interactions between idols and fans but also allow them to use decoration to shape the style of the idol image they desire in person, emphasizing or discovering the idol's unrevealed appeal.

For many K-pop fans, the narrative created by Hommas is indispensable within the fandom. It serves as a necessary piece of the idol’s story, reflects the idol’s popularity and status, and acts as a means of supporting the idol. These reasons drive some fans to become Hommas. Homma C decided to become a Homma because her beloved idol was embroiled in a scandal, causing significant damage to the idol’s public image. Many Hommas left the fan community out of disappointment at that time. Believing in her idol, Homma C decided to purchase a camera (Cannon 70-200mm f/4L USM) and set up a Homma account on X. Homma C felt that without Hommas, many moments where idols could be seen, especially concerts or fan signs, would go unnoticed. Moreover, she believed that idols without dedicated Hommas were at a disadvantage, as it indicated a potential loss of significant appeal from fans and market competitiveness. Therefore, she decided to become a Homma to show her support for her idol and to prove that her idol still had fans willing to dedicate their efforts and produce quality content. My interview J became a Homma of a new boy group in 2023. She was the only Homma of her idol at the time. When I asked J how she started to be a Homma in 2023, she answered, “It was kind of sad that my idol did not have any Homma to take his photo, so I decided to fill the job.” During my participation in fan activities in South Korea, many of my fellow fans decided to buy or rent an advanced camera to be a Homma, and the biggest reason was that their fan communities did not have a Homma or a satisfying Homma to take photos of their favorite idols.

Another characteristic that makes Homma’s format distinctive from individual fan encounters is its non-personal perspective. Homma’s real identity and individual fan experience are irrelevant to its content and often not encouraged. Viewers usually consume Homma’s works in a personalized way, using the photographs to fill in their imagination of the idol’s character contextualized in their version of the narrative, creating individual interpretations. Although fans might subsequently piece together the information listed in Homma photos into the collective narratives commonly built within the fan community, the process of appreciating Homma photos is inherently personal. Therefore, the posts published by Hommas typically refrain from sharing personal experiences or information related to the Homma themselves, aiming to minimize unnecessary discomfort, because what fans collectively resonate with is not about Homma’s personal experiences but the exploration of the idol’s charming personality. Suppose a Homma were to share personal interaction experiences. In that case, it can easily be perceived as reflecting a sense of superiority in having the chance to directly interact with the idols, which can be uncomfortable as a third party intervening in the para-social relationship between the fan and the idol.

Moreover, Hommas also avoid sharing their personal opinions toward the internal dynamics of relationships and episodes within the fan community to maintain a benign relationship with their followers and to prevent being intertwined into the intricate battles within the fan community, as such involvement could discourage the general fan’s consumption, and impair fans’ experience with their works, influenced by their mixed feelings toward the Hommas. This also explains why many Hommas are reluctant to accept interviews (Han et al., 2018; Kim, 2018; Lee & Ji, 2015). Such nonpersonal characteristics serve to distinguish Homma from other fan encounters, sharing details of individualized experiences. For most fans, Homma tends to be more of a service role, with the advantage of having more time and money than fellow fans who primarily consume the content, also because the core value of their photography is still dependent on the subject they are photographing-- the idols.

Homma's works often extend beyond internal fan sharing and reach audiences familiar with K-pop culture but outside the targeted fan community. As mentioned earlier, the Homma format is pervasive within the K-pop fan community and applicable to most individual fan communities. It serves as a translatable and commutable format across different K-pop audience circles. The general K-pop audience possesses a certain knowledge of the Homma format, which tends to be fancentric, offering diverse angles and perspectives distinct from official narratives. Many individual fans, particularly those with prior K-pop fan experiences, when getting a new K-pop fan community, actively search and follow Homma accounts on social platforms such as Twitter or YouTube to ensure a stable and relatively regular channel for consuming idol images or videos. The Homma format also allows new fans to grasp informal images of the idol to the official ones and get to know the shared narratives of the idol within the fan community. As mentioned, Homma’s content also plays a promotional role in reaching the public. If hashtags featured in Homma posts get on the hot trends on Twitter, ordinary users may click in and view the Homma images. Similarly, fans also actively use retweet functions to disseminate their favorite Homma photography within their social circles on online communities.

Conclusion

This study introduces a distinctive form of photography contextualized in the K-pop culture, the Homma format, which is different from the official content and the journalistic photos. Homma’s photography, as shot from a fan lens, conveys the affection between fans and idols. The Homma culture closely correlates to the K-pop industry’s core production model -- the creative industry of the idol narratives, as well as the geographical features and characteristics of the K-pop industry in Seoul. With the increasingly developed technology, as well as the affordability and accessibility of professional shooting equipment and software, non-professionals like Hommas can now proficiently master photography and photo-editing techniques. Fans no longer need to rely on official or journalistic materials to understand artists; instead, they actively engage in capturing their desired sides of the story on the very front, discovering the lesser-known aspects of their beloved celebrities, interpreting these images through their fan aesthetics, thus contributing to the narrative collectively shaped by the fan community, which is primarily differentiated form the official and journalistic narrative targeting toward the general public. The K-pop industry also enables fans to have more direct channels to get in touch with their beloved stars to create their version of the narratives, not only filling the gap but also competing against the formal ones.

Beyond what has been covered in this study, other aspects of Homma cultures are also worth exploring in depth in future research. Due to the publicity function of Hommas, numerous entertainment and broadcast companies attempt to collaborate with them to engage their audiences in fan activities and strengthen the fanidol relationship. Additionally, the worldwide popularity of the K-pop industry has led to an increasingly globalized K-pop fan culture. Homma culture has also started to emerge in other Asian countries, especially when foreign Hommas, who were initially active in Korea, return to their home countries to continue their activities in local fan communities. However, there have always been concerns about the power of Hommas, mainly due to the lack of regulation and control. Since Hommas, as fan photographers, frequently interact with idols and acquire substantial information, their statements hold significant credibility among fans, enabling them to question and overturn official narratives. When a Homma decides to leave the fan community and retaliate against their idols, their social media accounts can also become channels for releasing disruptive information, potentially leading to detrimental consequences for the idol’s future career.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

-

Batty, C. (2014). Me and you and everyone we know: The centrality of character in understanding media texts. In B. Thomas & J. Round (Eds.), Real lives, celebrity stories: Narratives of ordinary and extraordinary people across media (pp. 35–56). Bloomsbury.

[https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501306853.ch-002]

- Boorstin, D. J. (1992). The image: A guide to pseudo-events in America. Vintage.

- Cohen, D. E. (2014). Seoul’s digital media city: A history and 2012 status report on a South Korean digital arts and entertainment ICT cluster. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 17(6), 557–572.

-

Fa, Z. (2019). A study on the fandom activities of the Korean idol group of Chinese students studying in Korea -Focused on fan page operators- [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Chung-Ang University.

[https://doi.org/10.23169/cau.000000230662.11052.0000464]

-

Fairchild, C. (2007). Building the authentic celebrity: The “idol” phenomenon in the attention economy. Popular Music and Society, 30(3), 355–375.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/03007760600835306]

- Gabler, N. (2001). Toward a new definition of celebrity. The Norman Lear Center.

-

Han, S., Yoon, Z., & Lee, J. (2018). A multi-method approach to activities of ‘Photaku’: Photo-taking fans in the Korean entertainment industry. ASONAM 2018: Proceedings of IEEE/ ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (pp. 755–758). IEEE.

[https://doi.org/10.1109/ASONAM.2018.8508432]

- Harris, R. (2022). Murray stories and Keanu memes: The role of offline encounters in online celebrity identity construction. In C. Lam, J. Raphael, R. Middlemost, & J. Balanzategui (Eds.), Fame and fandom: Functioning on and offline (pp. 147–161). The University of Iowa Press.

- Hong, S.-K. (2017). Hallyu beyond East Asia. In T. J. Yoon & D. Y. Jin (Eds.), The Korean wave: Evolution, fandom, and transnationality (pp. 67–86). Lexington Books.

-

Horton, D., & Wohl, R . R . (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction. Psychiatry, 19(3), 215–229.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049]

- Howe, P. (2005). Paparazzi: And our obsession with celebrity. Artisan Books.

- Howells, R. (2011). Heroes, saints and celebrities: The photograph as holy relic. Celebrity Studies, 2(2), 112–130.

- Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York University Press.

- Jung, M., & Lee, N. (2009). Fandom managing stars, entertainment industry managing fandom. Media, Gender & Culture, 12, 191–240.

- Kang, J., & Kang, J. (2016). Bbasunineun mueoseul galmanghaneunga? [What do Bbasuni desire?]. Person & Idea.

-

Kim, J. (2018). “Home” and “Homma” in K-Pop fandom: From fan sites and paparazzi to black market and cultural producers. Journal of Culture Industry, 18(3), 1–10.

[https://doi.org/10.35174/JKCI.2018.09.18.3.1]

- Lee, D. (2023, May 5). Where do ‘fans’ and ‘idols’ stand in the K-pop idol ecosystem?: [K-pop diary] What happens if entertainment platforms dominate ‘fandom activities’ too? Pressian. https://www.pressian.com/pages/articles/2023050410153252086

- Lee, H.-Y., & Ji, H.-M. (2015). A research on discriminations inside fandom in Korea— Focusing on fan producers in tweeter activities. Media, Gender & Culture, 30(4), 5–40.

- Lee, J.-S. (2019, December 15). “Truly frightening” BTS V’s remarks rekindle debate on Sasaeng fans and Homma culture. Sports Seoul. https://www.sportsseoul.com/news/read/861240

-

Linkof, R. (2020). Public images: Celebrity, photojournalism, and the making of the tabloid press. Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003103868]

- López Del Valle, N. (2021). Lights, camera, action! Defining the idol in contemporary Asia [Master’s projects and capstones]. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/1186

-

Mortensen, M., & Jerslev, A. (2014). Taking the extra out of the extraordinary: Paparazzi photography as an online celebrity news genre. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 17(6), 619–636.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877913503425]

- Namu Wiki. (n.d.). Yuqi ((G)I-DLE). In Namu Wiki. Retrieved May 18, 2024. https://namu.wiki/w/우기((여자)아이들)

- Nate Pann. (2020, December 11). Naegijun hommasajin lejeondeu yeodolpyeon [In my opinion, legendary fansite photos: Female idols edition]. https://pann.nate.com/talk/356073173#replyArea

- Oh, J. (2019, December 7). Idol paparazzi rivaling presidential coverage, ‘Homma’. Chosun Ilbo. https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2019/12/06/2019120602273.html

- Ramamurthy, A. (2021). Spectacles and illusions: Photography and commodity culture. In L. Wells (Ed.), Photography (pp. 265–326). Routledge.

- Squiers, C. (1999). Class struggle: The invention of paparazzi photography and the death of Diana, Princess of Wales. In C. Squiers (Ed.), Over exposed: Essays on contemporary photography (pp. 269–304). New Press.

- Tataru, L. (2012). Celebrity stories as a genre of media culture. Journal of Teaching and Education, 1(6), 15–21.

- Thomas, B. (2014). Fans behaving badly? Real person fic and the blurring of the boundaries between the public and the private. In B. Thomas & J. Round (Eds.), Real lives, celebrity stories: Narratives of ordinary and extraordinary people across media (pp. 171–185). Bloomsbury.